At the end of the 1980s, Klaus Jung's interest in teaching at an art academy grew. A position was advertised at the small but committed art academy in Trondheim – and although Norway was unknown to him at the time, he was attracted by the idea of leaving the Düsseldorf art scene and getting to know new contexts. The original plan: a short trip abroad. But this turned into 13 years in Norway and later 7 years in Scotland.

Trondheim 1989 – 1995

In Trondheim, a second studio is initially set up parallel to the space in Düsseldorf. However, it soon became clear that the stay would not be a short intermezzo. The excellently equipped workshops at the art academy enabled him to continue working productively with wood and metal. Gradually, however, the focus shifted from the object to the image. The image has always been part of the sculpture – as content, as background, as reference. Now it should speak for itself.

A few months after his arrival, the then Rector of the Academy announces his resignation. Klaus Jung agreed to take over as director – a decision that was supported by the faculty and characterised his further artistic and institutional career.

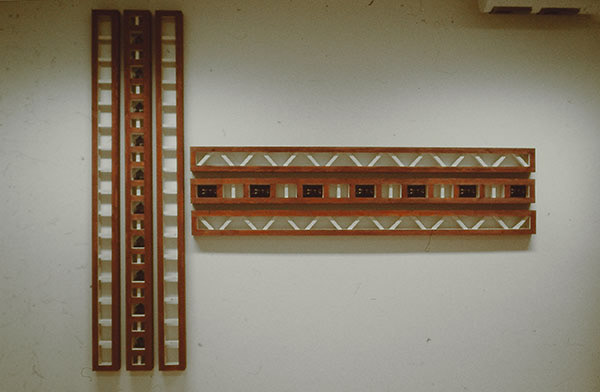

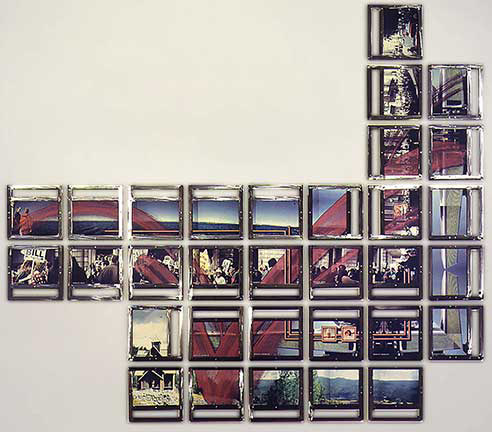

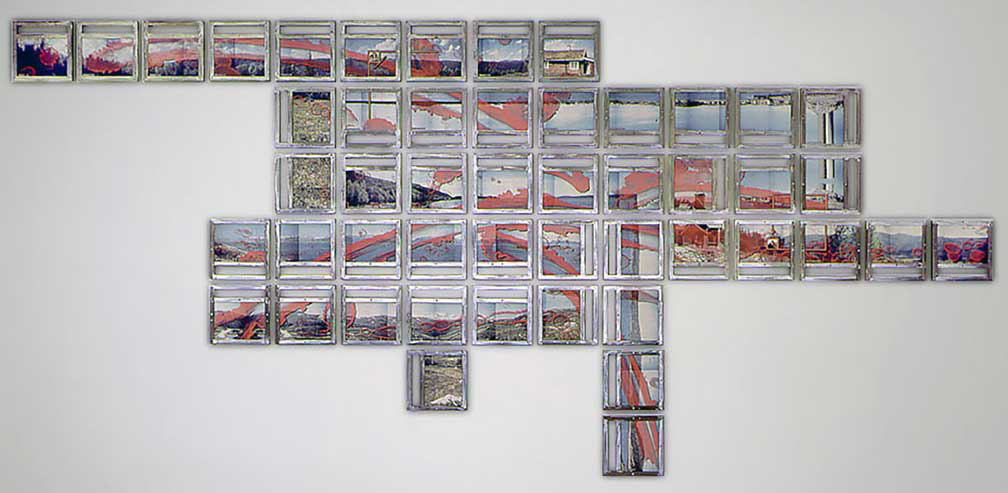

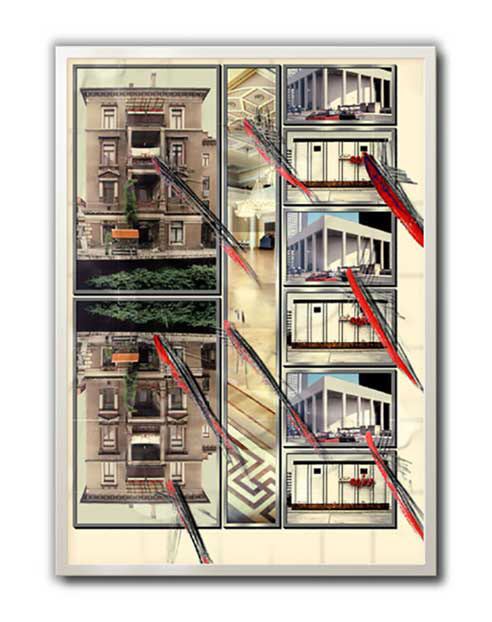

Red Sculptures (1990)

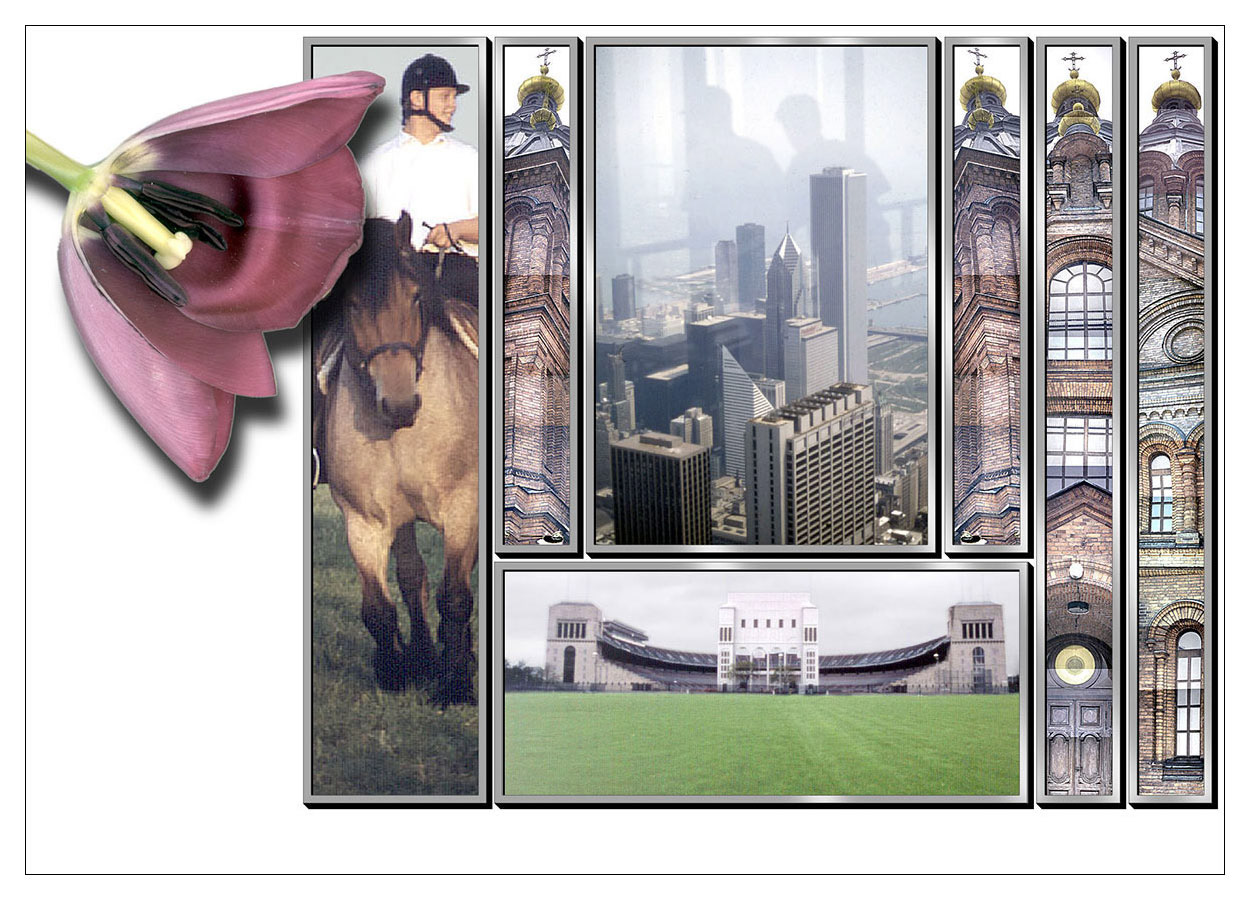

In the early years, the principle of the façades and chairs from the Düsseldorf period was continued. Photo series and television stills are inserted into wooden constructions that look like oversized frames – image-supporting, interpretative, limiting. The first collages behind glass are created. An exhibition of the teachers in the old mining town of Røros marked – albeit unconsciously – a farewell to sculpture.

Mirrors (1990-1991)

The image archive built up from TV screenshots grows. Instead of classic collages, photo sequences now appear on mirrors. Incised patterns reveal the mirror background – viewers see themselves in the centre of the image. Such works are shown in the studio in Trondheim, in Düsseldorf and in 1991 in the Klingenmuseum in Solingen, where they are again juxtaposed with a group of sculptures.

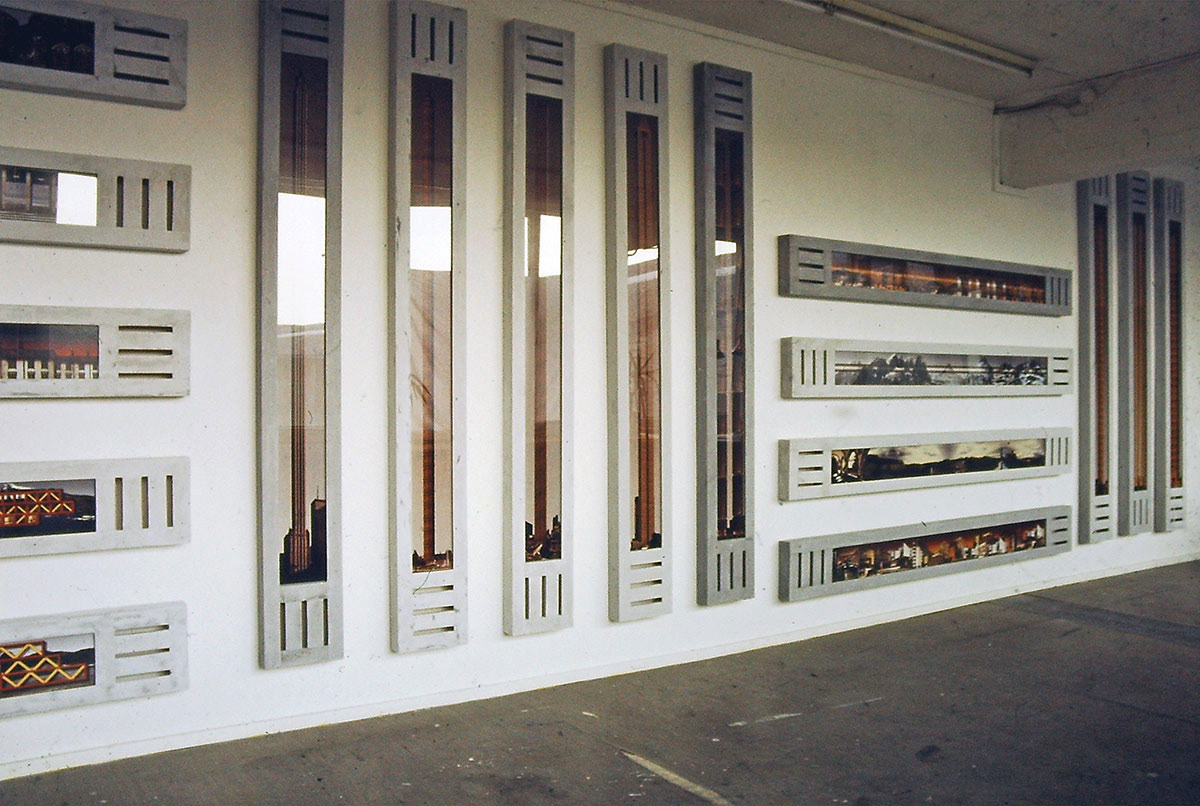

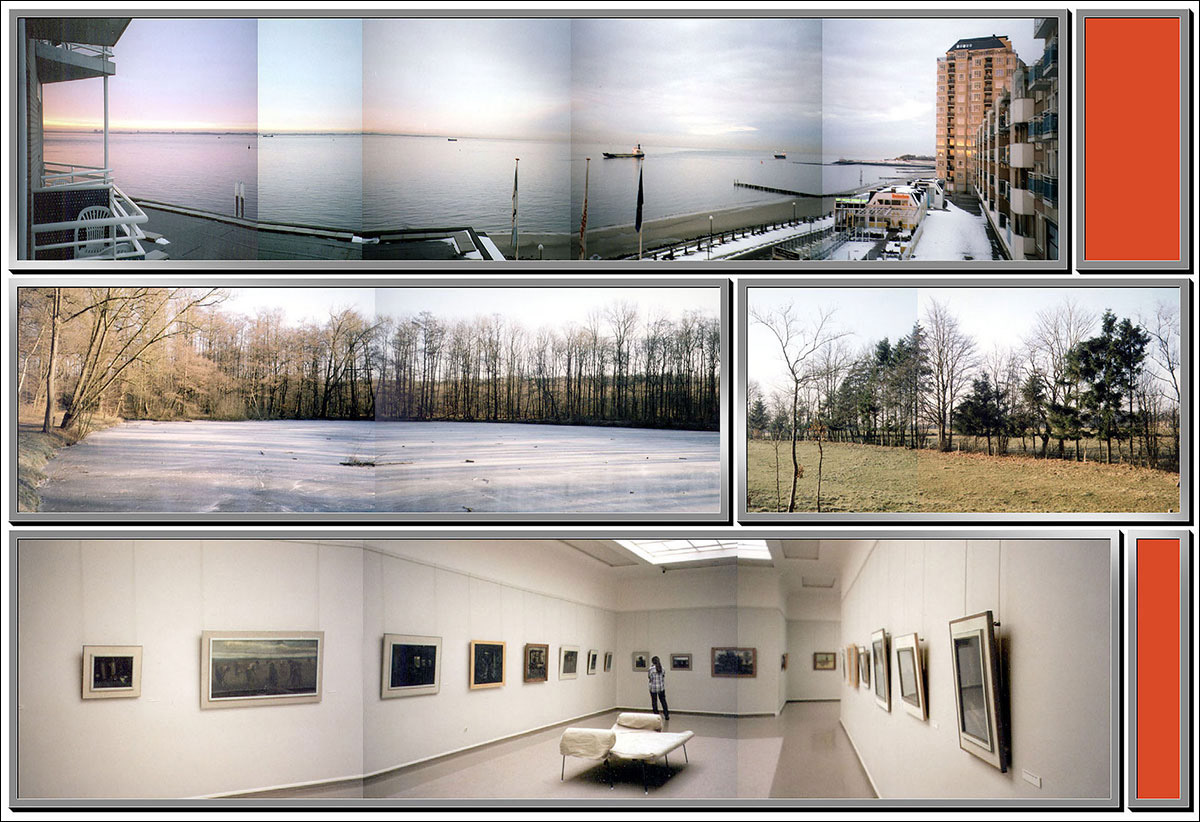

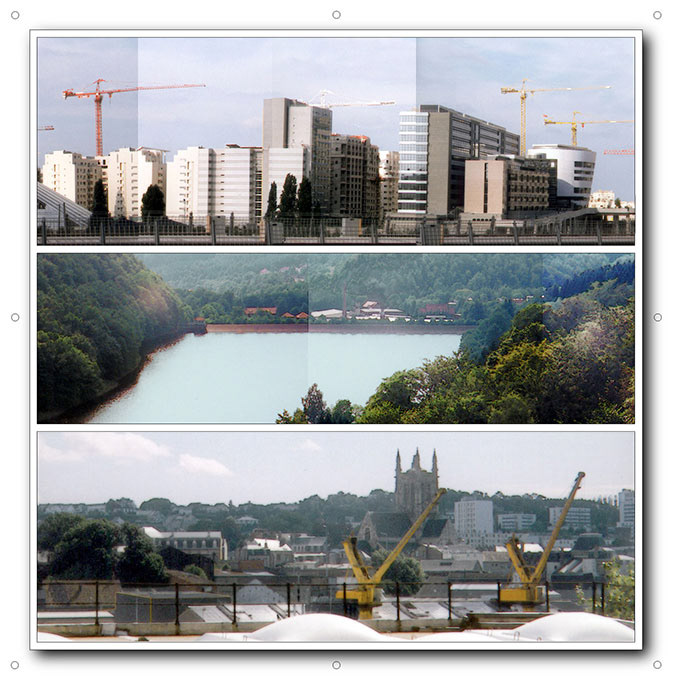

Horizons (1992)

With access to digital image processing programmes at the art academy, a new work phase begins. Horizon lines, iconic architecture and real landscapes are transformed into digital panoramas, distorted and extended. The Horizons series, exhibited in the Düsseldorf studio in the summer of 1992, plays with linear stretching, graphic abstraction and the question of pictorial depth in digital space. The frames – grey-painted wooden boxes – preserve a sculptural moment.

Memories (1993)

An exhibition at the Trondheim Art Museum expands the digital experiments. Landscapes are bent, 3D simulations incorporated, performative self-portraits integrated. Images remind us – but of what exactly? The question of truthfulness recedes into the background. The exhibition space is structured by symmetrically mirrored picture arrangements, plaster and wooden frames give the works body.

Noticeboard (1993)

As part of a fellowship at Ohio State University (USA), a large-format picture installation of black and white laser prints was created – hung in a grid, determined by a dice roll, partially painted over. The wall of notes is mounted on plasterboard, which is later cut up and reused in other works: e.g. in a portico installation (porch) as a reference to typical American house entrances.

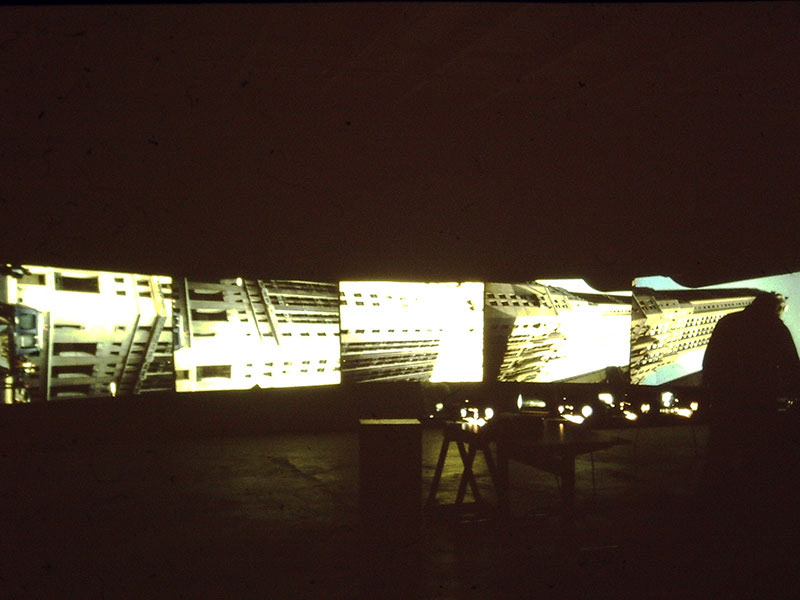

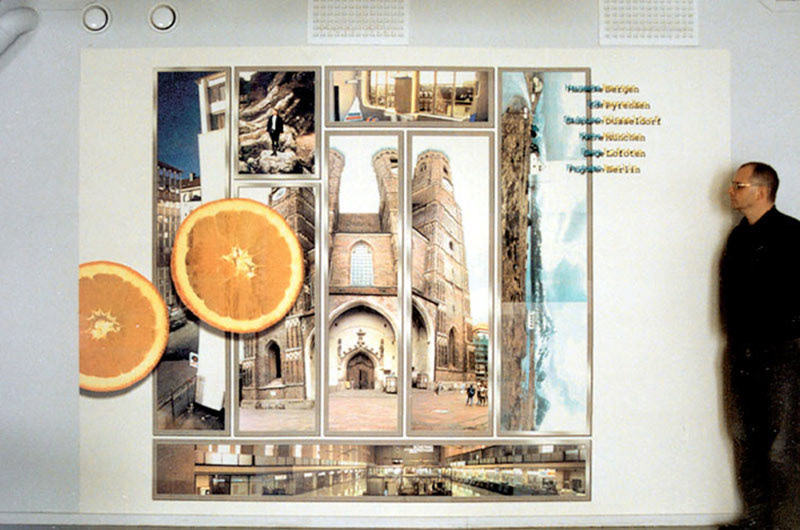

Projections (1994)

A journey of several weeks through the USA becomes the starting point for a new way of working. Slides replace the sketchbook. In a performative installation, five slide projectors are switched manually. Repetition, mirroring, sequential image strips – supported by the rhythmic clicking of the projectors – create an idiosyncratic dramaturgy in the dark room.

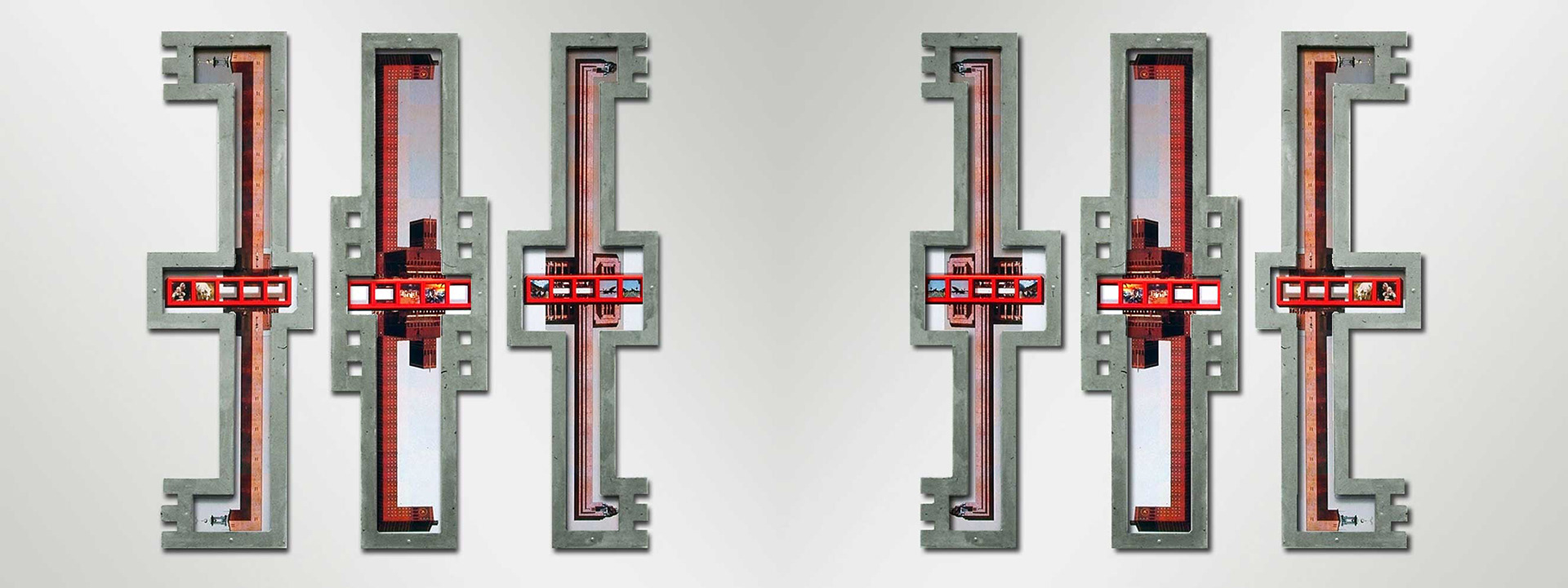

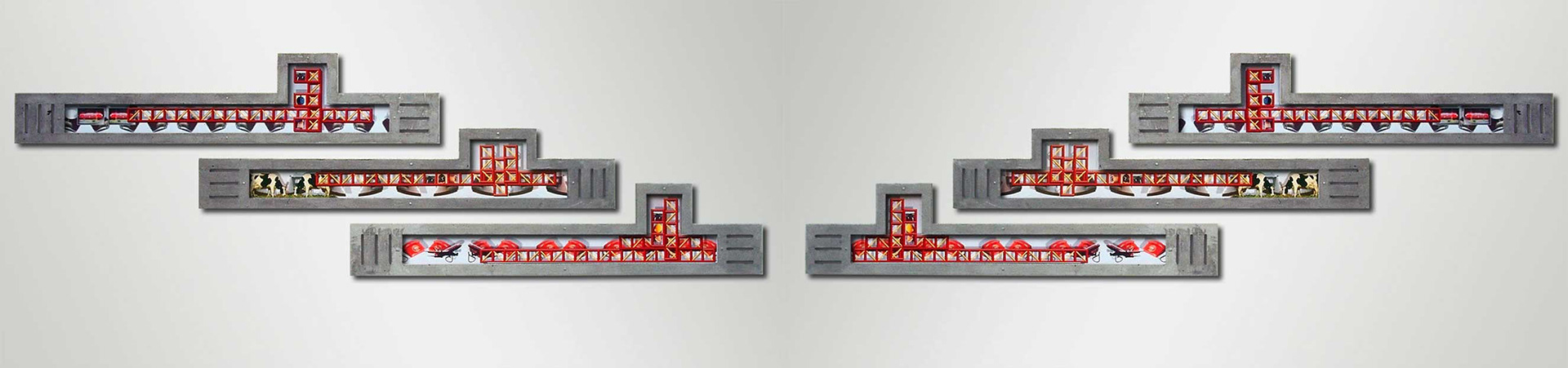

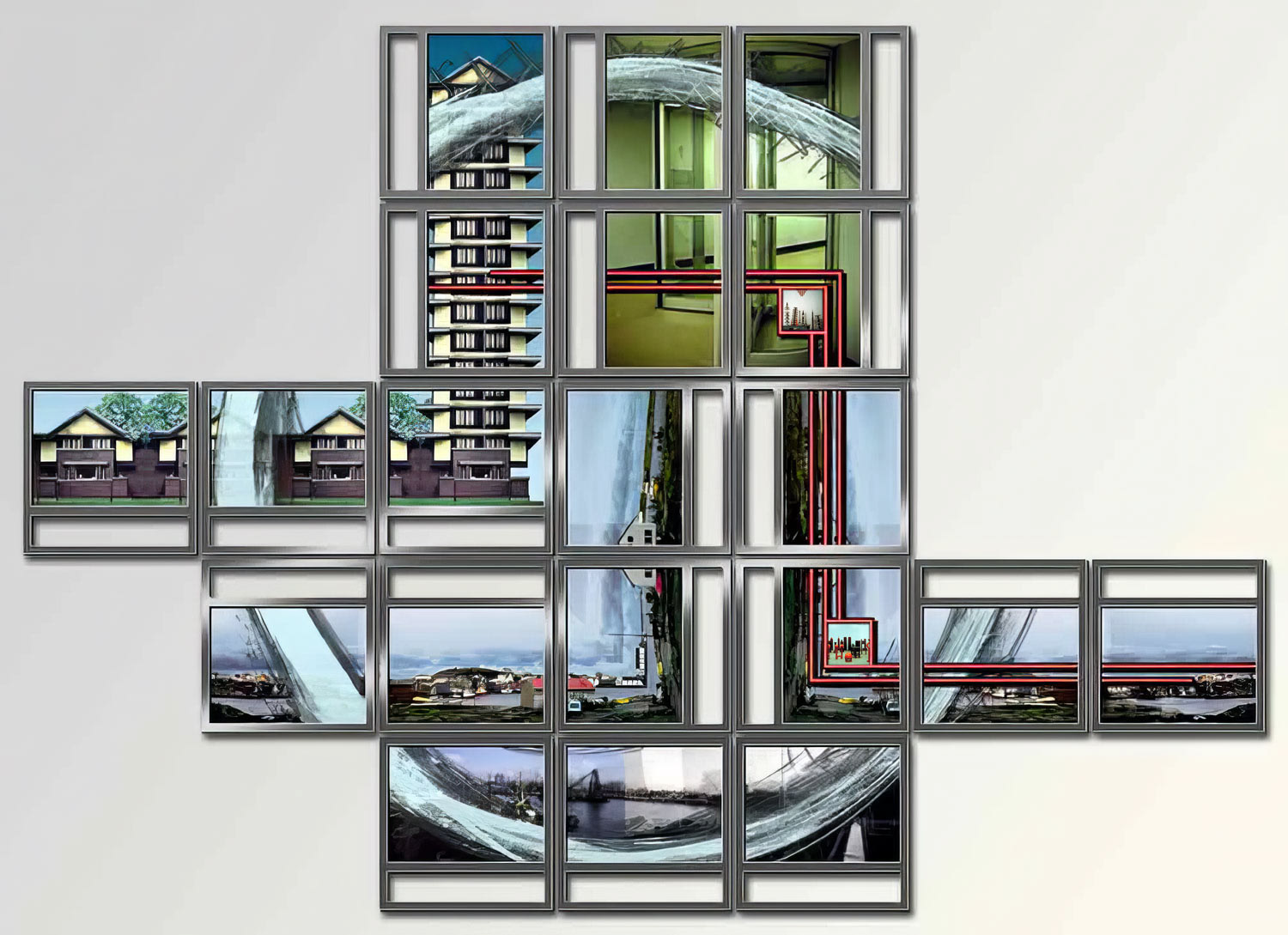

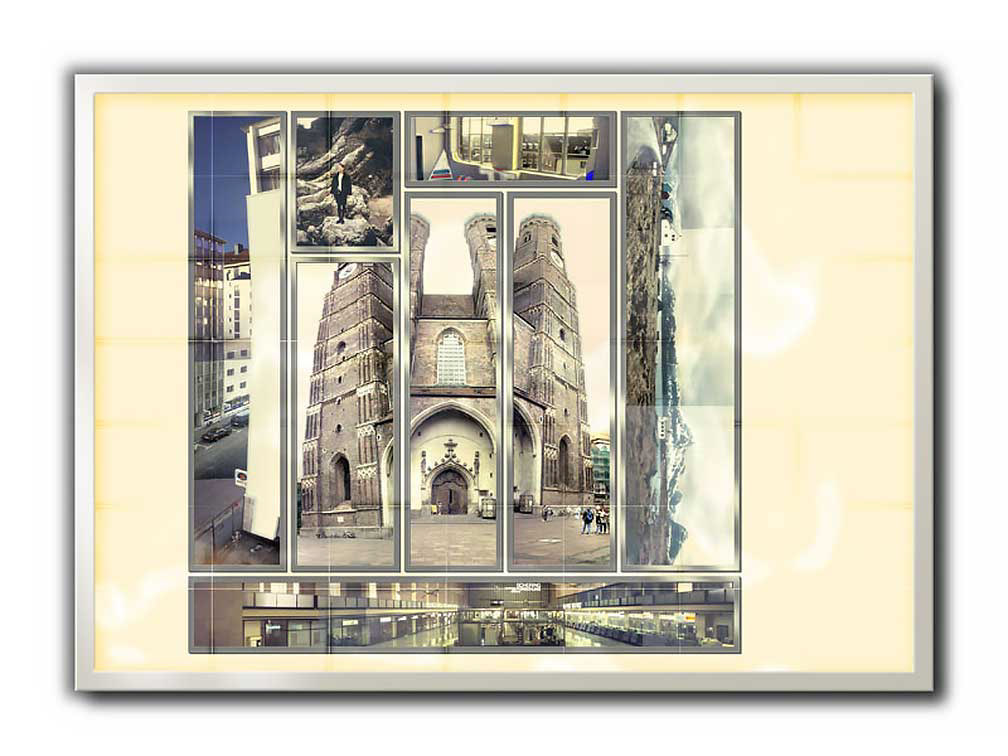

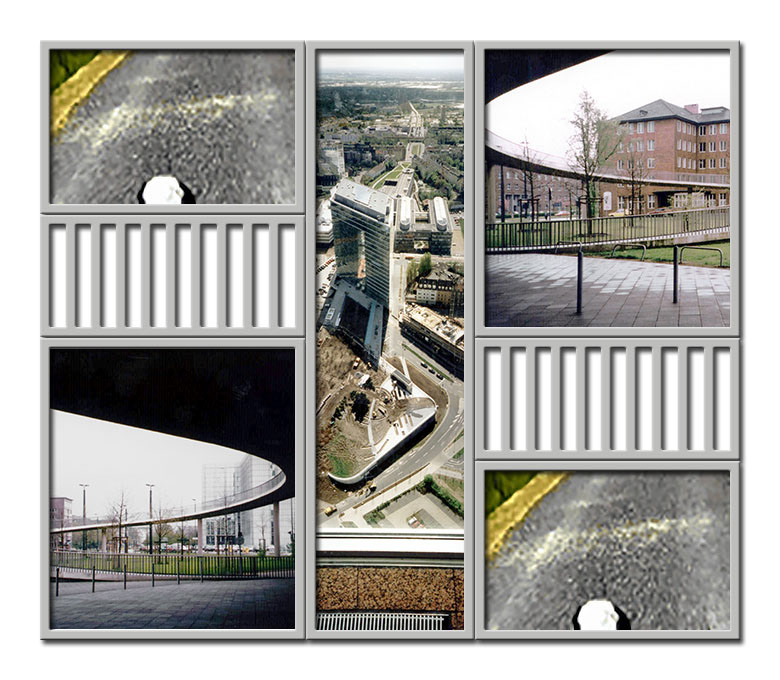

Gray Line (1995-1996)

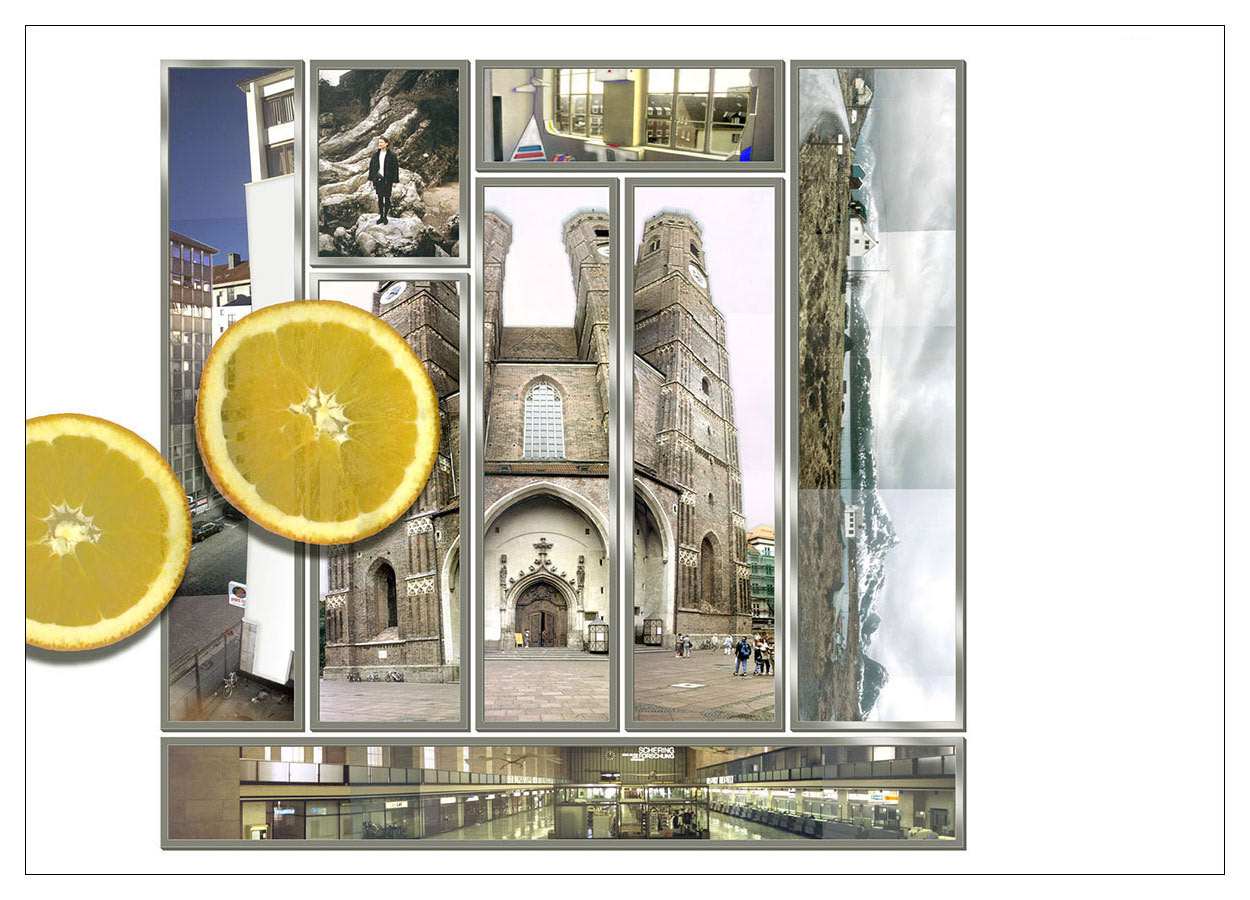

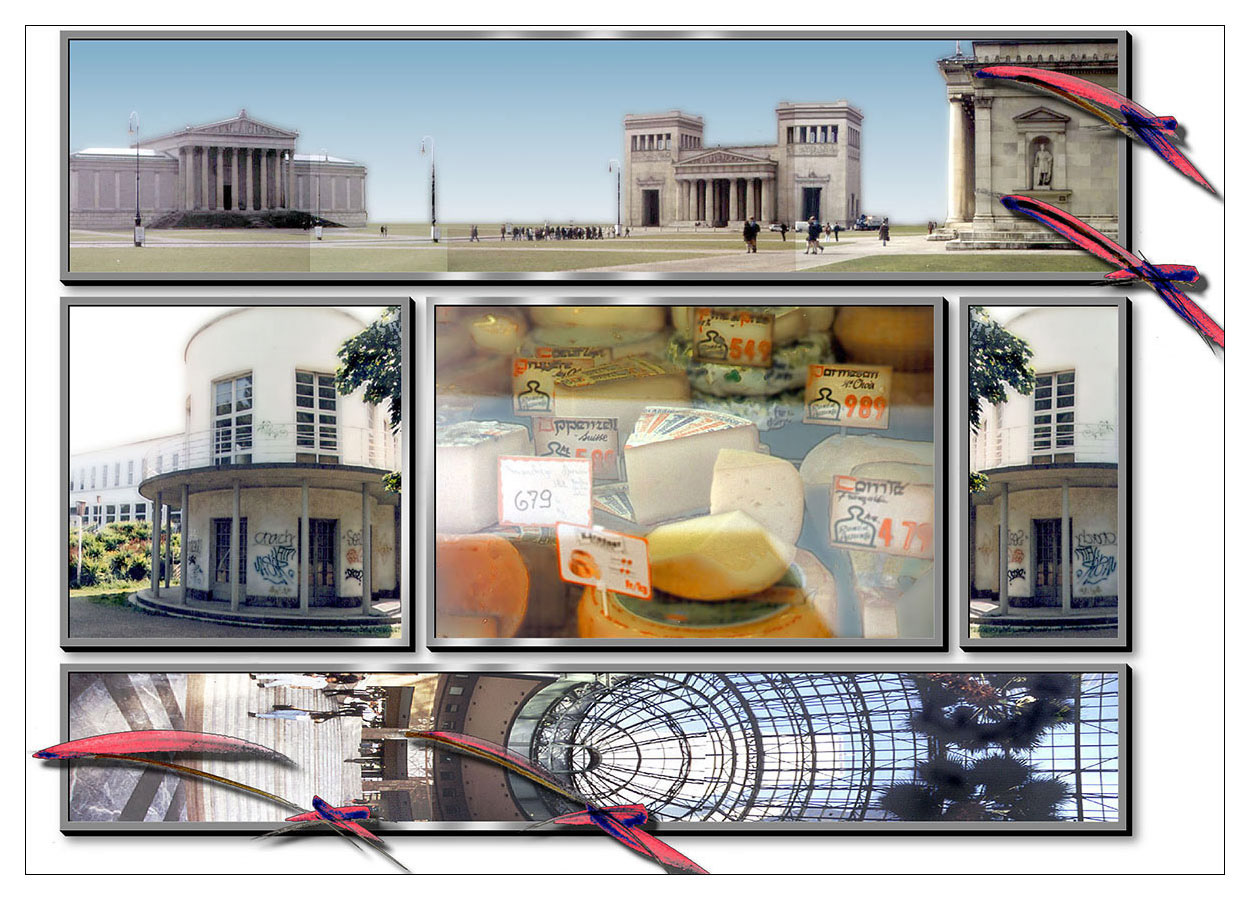

Named after the sightseeing bus system in many US cities, this series digitally processes photographs of the USA: architectural images are stretched, panoramas remounted. A steel frame with a characteristic slit – top, bottom, right or left – is placed on each image. The 303 frames are screwed together in a monumental wall panel (15m × 3m), first shown in 1995 in the project hall of the Trondheim Art Academy, later in the Lenbachhaus in Munich.

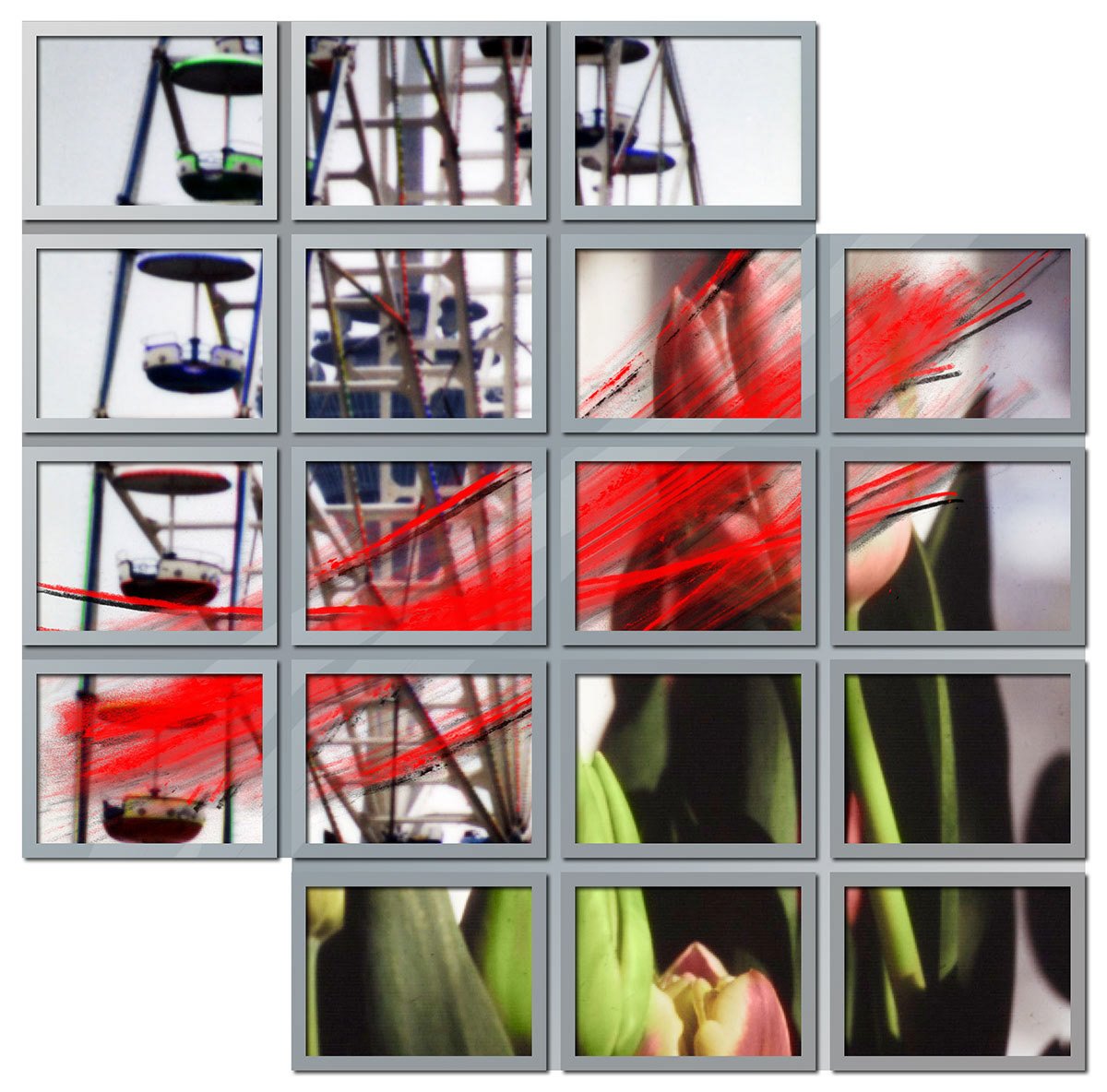

Persistent Disturbance (1995)

A series of sixteen works, also gridded in steel frames, develops the principle further. Repetitive images, gestural overlays, digital deformations and graphic interventions deliberately disrupt the understanding of the image – a reference to the negotiable reality of digital representation.

Hinged (1995)

Two photographs are squarely enlarged and intertwined. Rough graphic overdrawings irritate the expectation of visual clarity. The inkjet prints in A4 format are framed to form a large whole (approx. 180×180cm). A selection was exhibited at the Kunstverein Oslo in 1995.

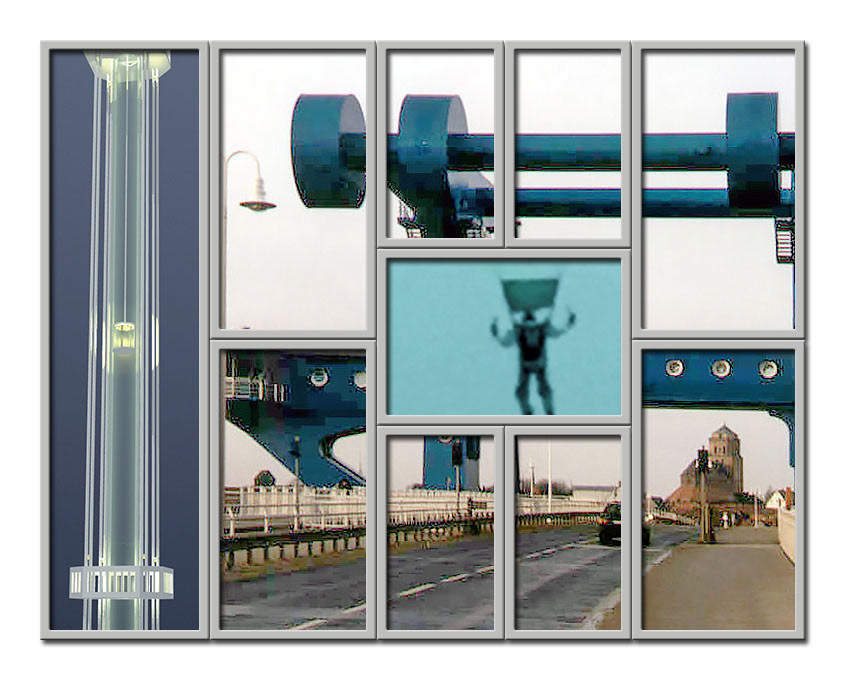

BERGEN 1990- 2002

After two terms as rector of the Trondheim Art Academy, Klaus Jung is asked by the Bergen Art Academy to take over responsibility for the first-year students on a temporary basis. Another move follows, and a new studio is set up in a room at the art academy. Access to digital technologies – computers, image editing software and printers – improves significantly, especially as working at an art academy supports and accelerates such developments. Artistic attention increasingly shifts to the photographic image.

A comprehensive university reform begins in Norway at this time. The small, previously independent art academies are to be merged into larger units. In Trondheim, the Academy of Fine Arts becomes part of the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Technology and Natural Sciences (NTNU). In Oslo and Bergen, new state art academies will be created by merging with design and arts and crafts schools. Klaus Jung is asked to help shape and support this process in Bergen as rector.

He sees the management of an art college as an artistic task – conceptually, processually, in dialogue. Special attention is paid to the development of international networks: during this time, he is also involved in a Scandinavian co-operation between art academies and participates in the European League of Institutes of the Arts.

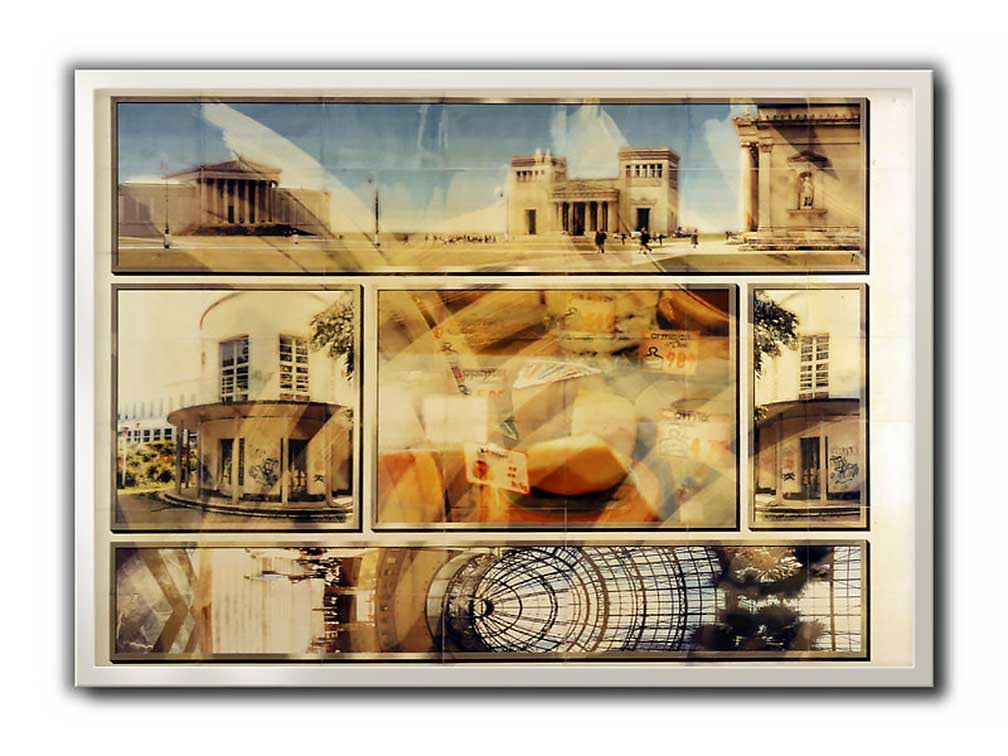

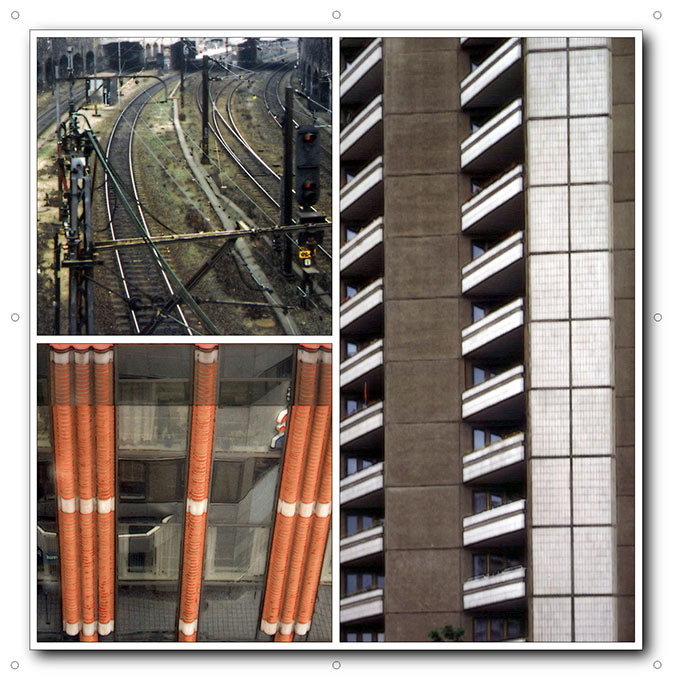

Exercises (1996)

Large-format colour prints were neither easily available nor affordable in the early 1990s. In order to be able to realise larger image formats, digital files are divided into A4 formats and printed on standard household inkjet printers. The individual sheets are then precisely assembled.

From 1996, the steel frames that still refer to the three-dimensional work disappear. Instead, "fakes" were created: images were rotated, repeated, juxtaposed – sometimes slightly shifted. In this way, new pictorial contents are created that refer to real places or objects, but are detached from the archive context through the combination. For the first time, pure colour surfaces are also used as independent pictorial elements.

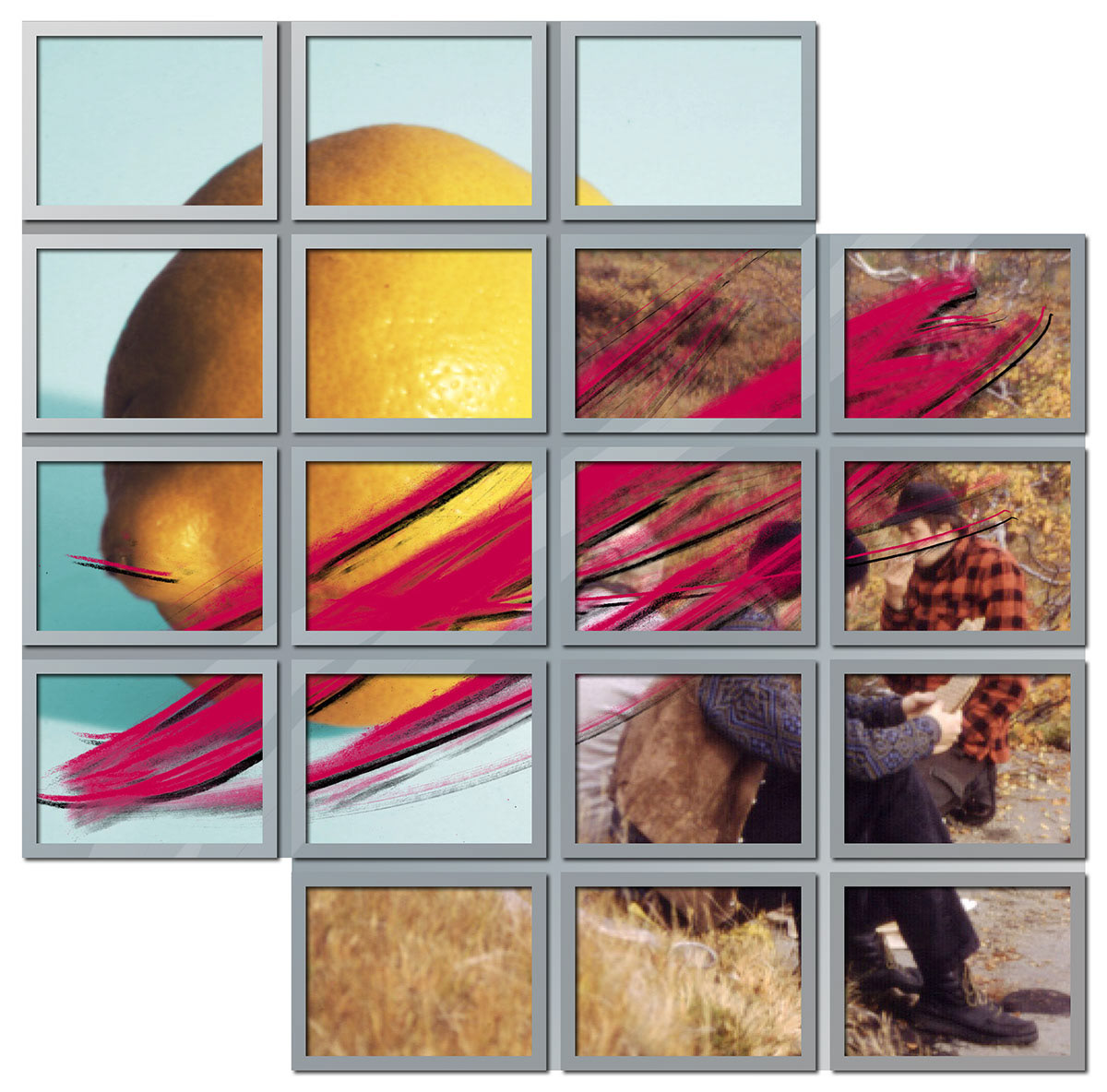

Malfunctions (1996)

In a next step, the pictorial compositions are deliberately disturbed – by superimposed drawings, scanned objects, traces of colour and digital fragments. In this way, the images elude clear legibility. Associative layers are created that oscillate between documentation, reflection and intervention.

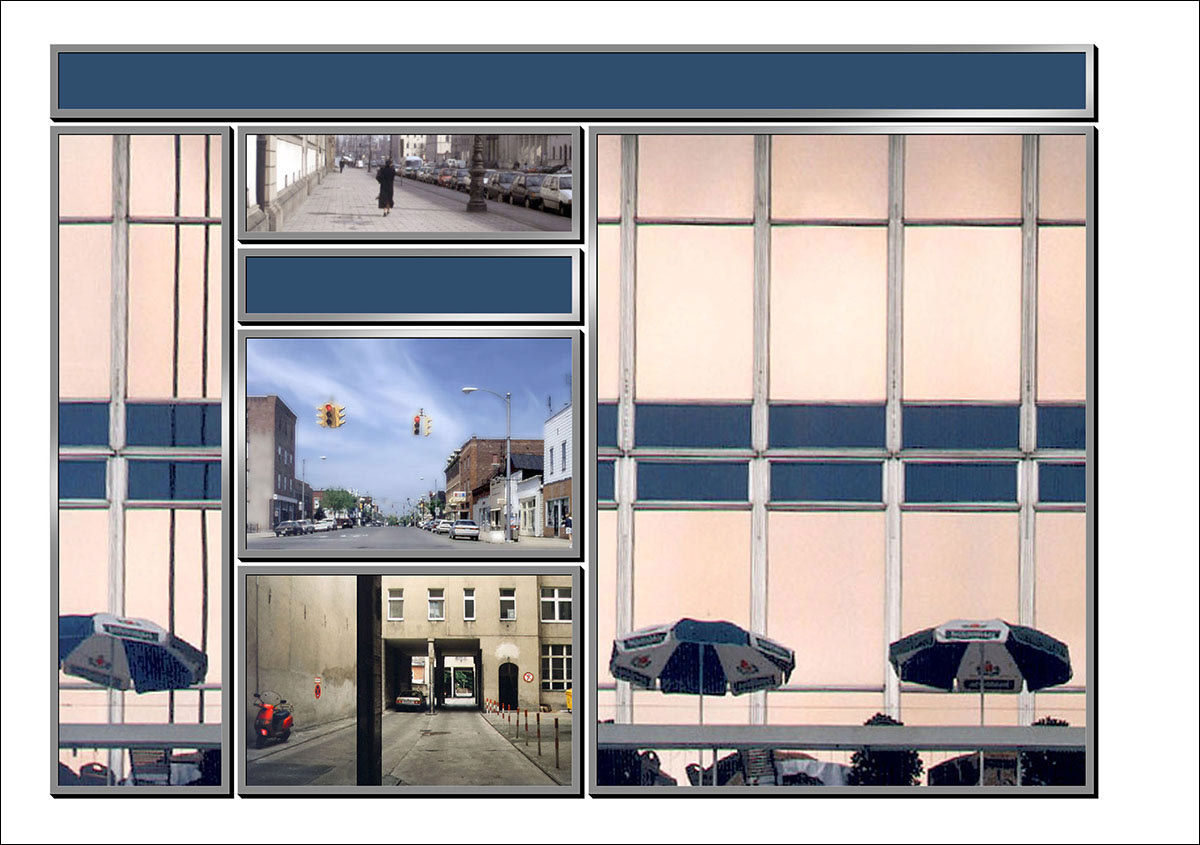

Walls (1997)

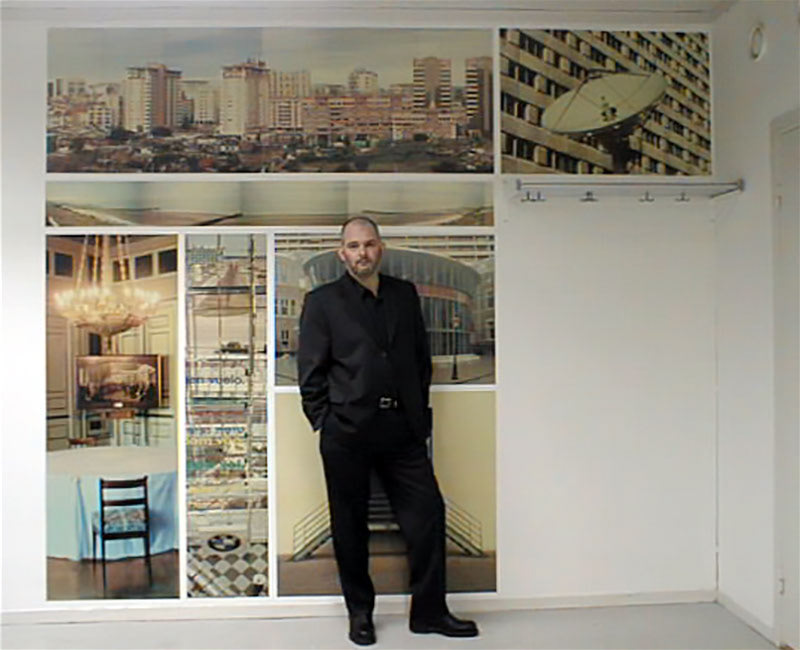

The technique of assembling large-format works from many A4 printouts also allows wall-sized installations. The individual sheets are applied directly to the wall with wallpaper paste – a pragmatic but effective approach to the visual archive. Such wall works were created from 1997 onwards.

Chlorine pictures (1997)

Here the picture surface is additionally irritated by chemical processes: The printed individual sheets are glued onto large carrier plates and then treated with chlorine. The active ingredient dissolves the printing ink unevenly and creates bleaching structures on the surface. To fix this state, a layer of boat varnish is applied. This creates a balance between chance and control.

Album 98 (1998)

For the first time, an attempt is made to present the digital image directly on the screen rather than by printing it out. In an early form of animation, the images are pushed through the format at defined intervals – the viewer loses control of the viewing speed, the time is determined by the image itself.

The animation is accompanied by short pieces of music from a collection of alternative pop music. As with an LP, the twelve tracks are structured on a "front and back". Album 98 is conceived as a conceptual image-music composition – for individual viewing or as an overall experience.

A planned presentation in a specially designed screen library could not be realised. The original files can no longer be played today – only still images have been preserved.

Album 99 (1999)

The combination with music proves to be problematic: too dominant, too fixed in expression. For Album 99, therefore, ambient sounds are used – sound recordings from public spaces, analogous to the photographic collection. Short video sequences complement the animations.

But here, too, access remains fragmentary: technical developments prevent subsequent playback, and many files have been lost due to storage on CDs.

Individual still images and a small accompanying book with images and travel texts have been preserved, reconstructing the original presentation in documentary form.

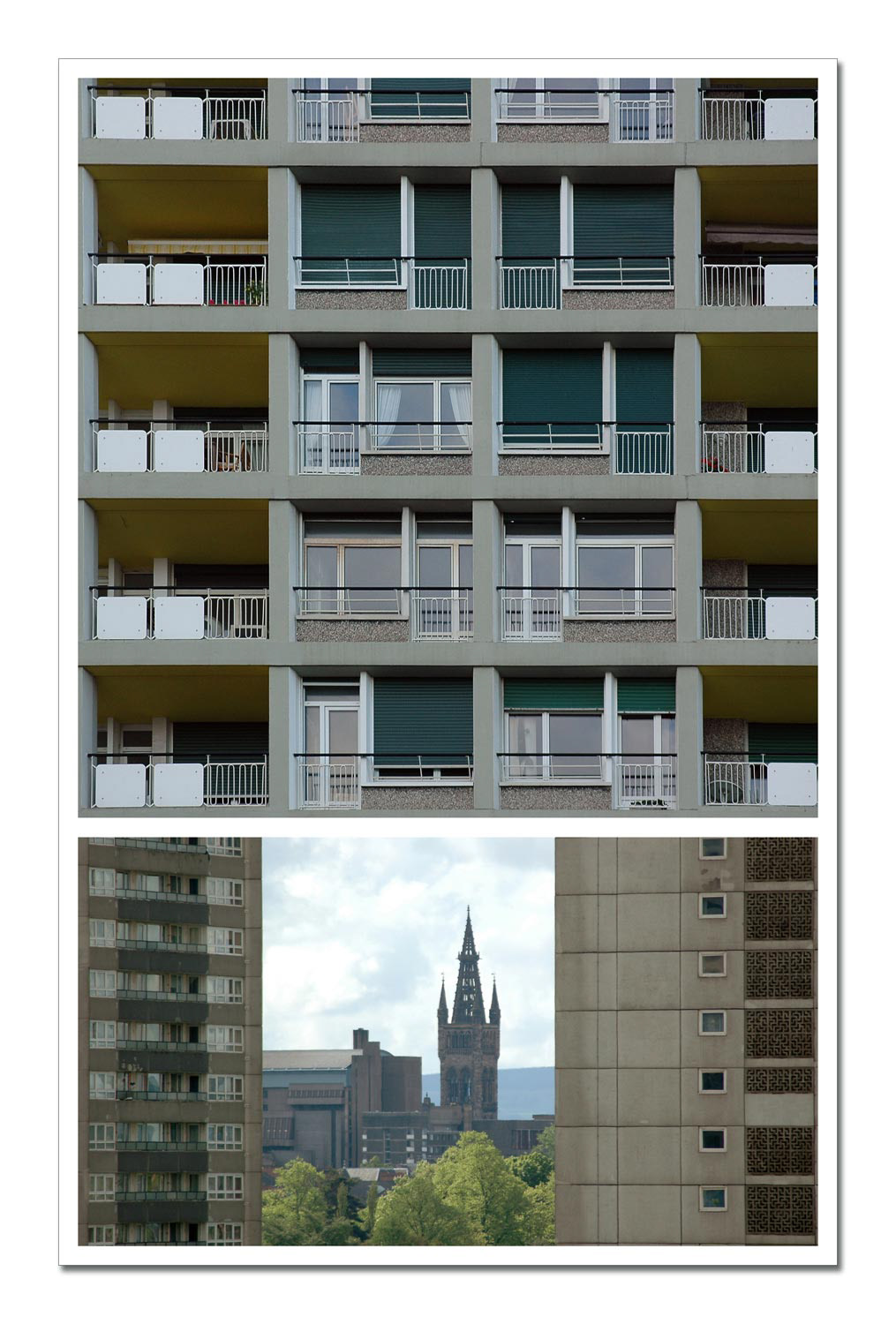

Glasgow 2002 – 2009

Klaus Jung's time in Norway also ends with the end of his second term as headmaster in Bergen. A return to teaching after a sabbatical is not realised – instead he takes over as Head of the School of Fine Art at the Glasgow School of Art. The new studio in the legendary Mackintosh Building also serves as a workspace, office and conference venue.

On 23 May 2014, the building was badly damaged in a devastating fire. Numerous final projects were lost, but thanks to effective evacuation measures, the disaster did not cause any personal injury. Klaus Jung remembers later:

"I am saddened by the exam papers that were destroyed by the fire. I admire the team of teachers [...] and have great respect for the firefighters who immediately began to rescue – the Mackintosh heritage as well as the young art."

The Mackintosh Campus Appeal was set up to support the rebuild – over £20 million was raised and the building was restored. But in 2018, there was another fire – so severe that the future of the building remained uncertain. The cause of the fire can no longer be determined. The GSA's board of directors continues to pursue the goal of restoring the building to its original state – but it is unclear whether and how this project can be realised in 2025.

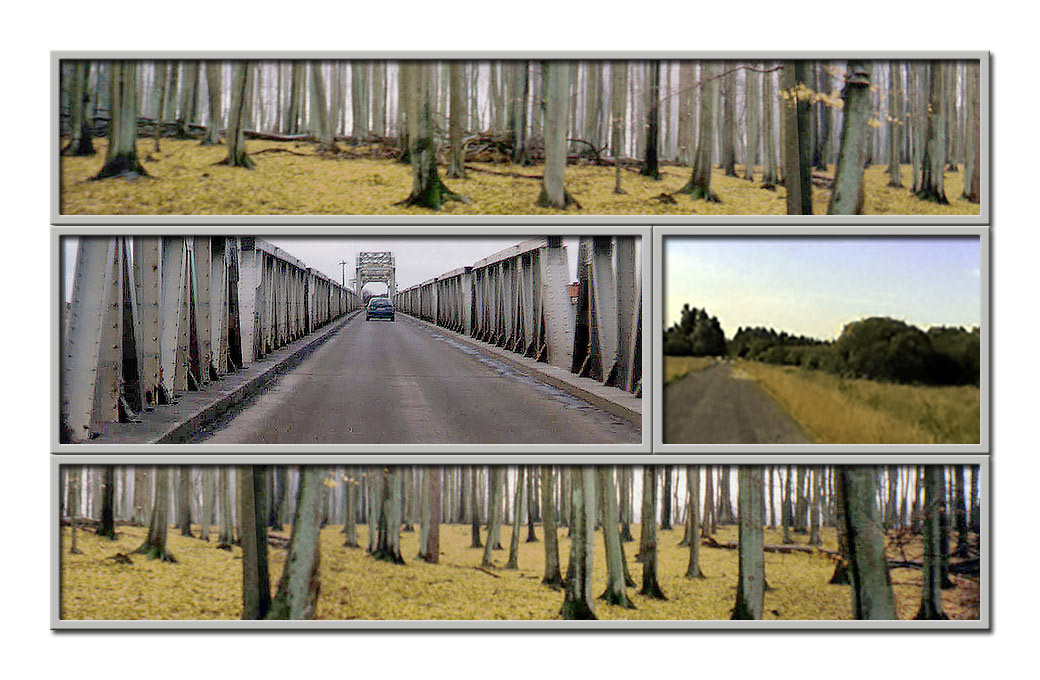

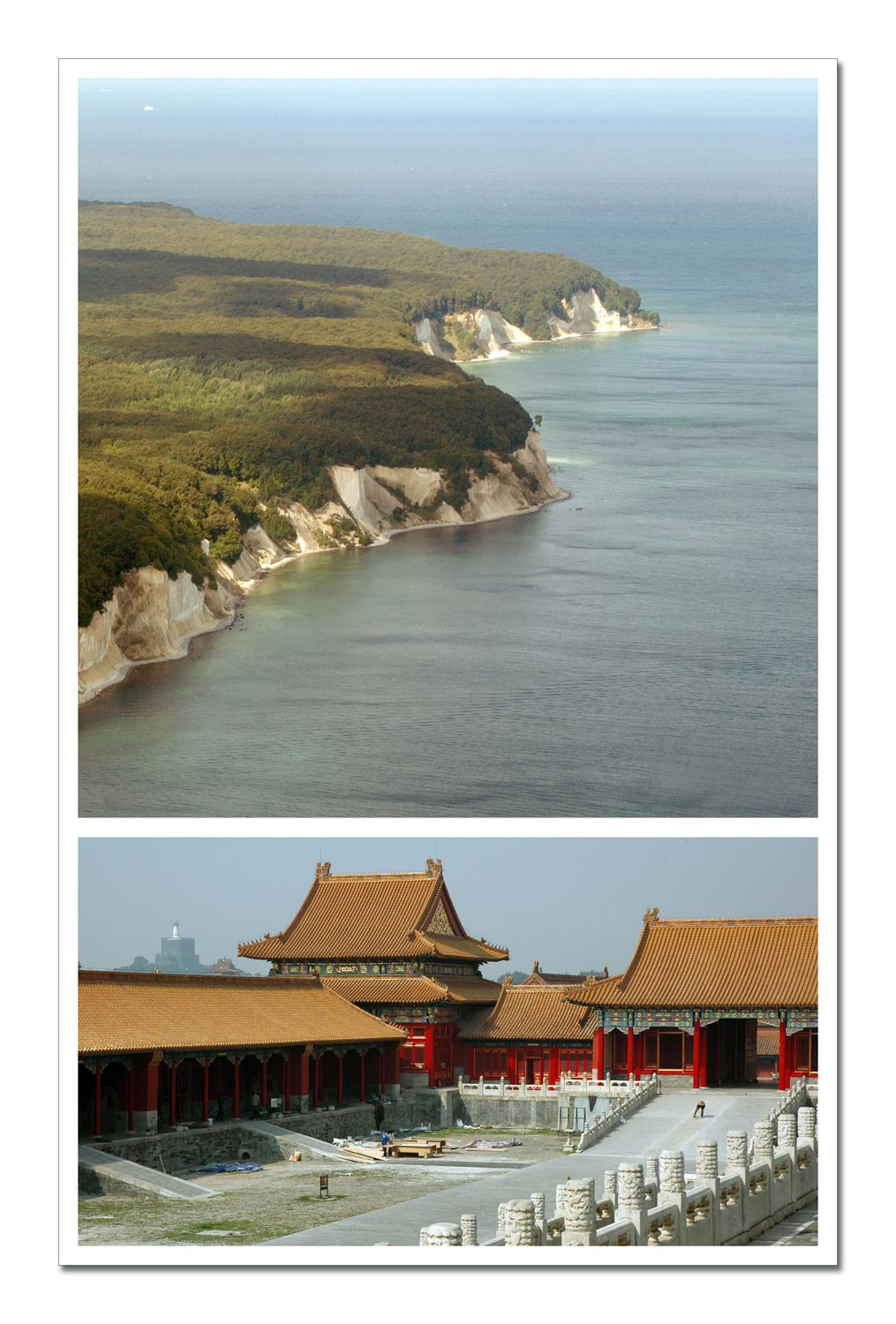

As early as 1997, the photographic image moved to the centre of his artistic work. Klaus Jung began to build up a digital image archive – collecting while travelling, or travelling in order to be able to collect. The subjects are unspectacular: architecture, landscape, everyday life.

Starting with scanned colour prints, later digitised slides and from 2000 with digital cameras, the archive grew to around 25,000 images by 2014. Many of these are panoramas, assembled from individual shots. By 2023, the collection comprises more than 75,000 files – only a fraction of which are included in the work series.

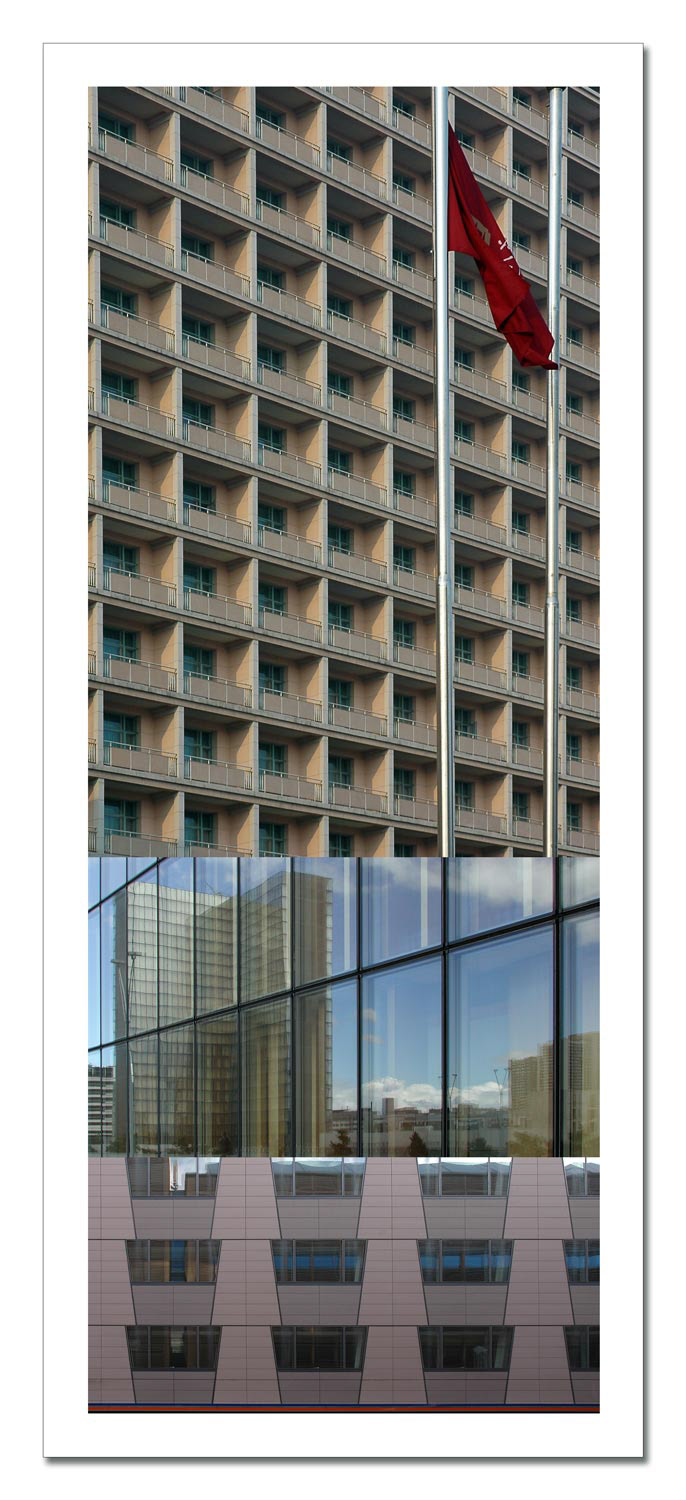

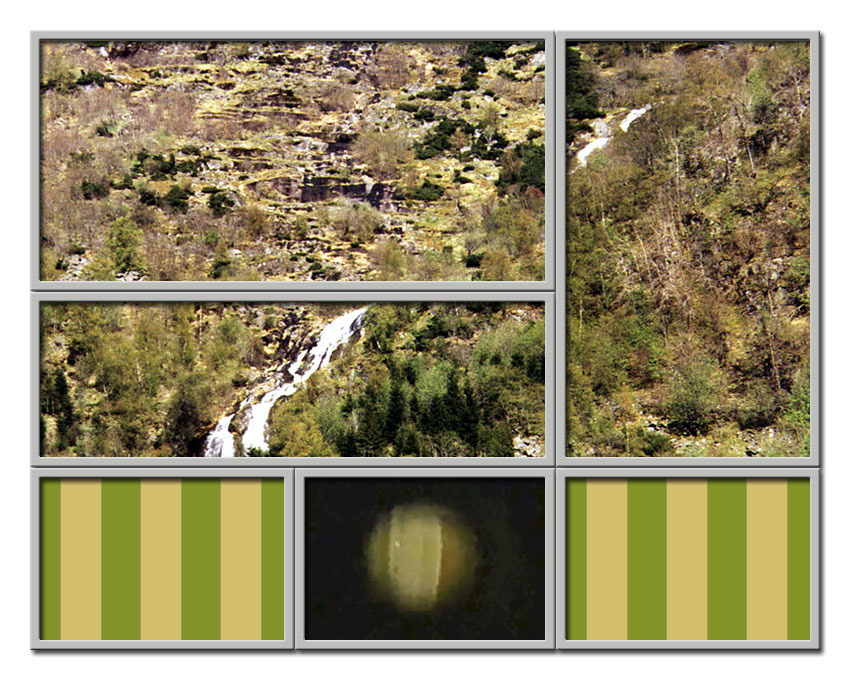

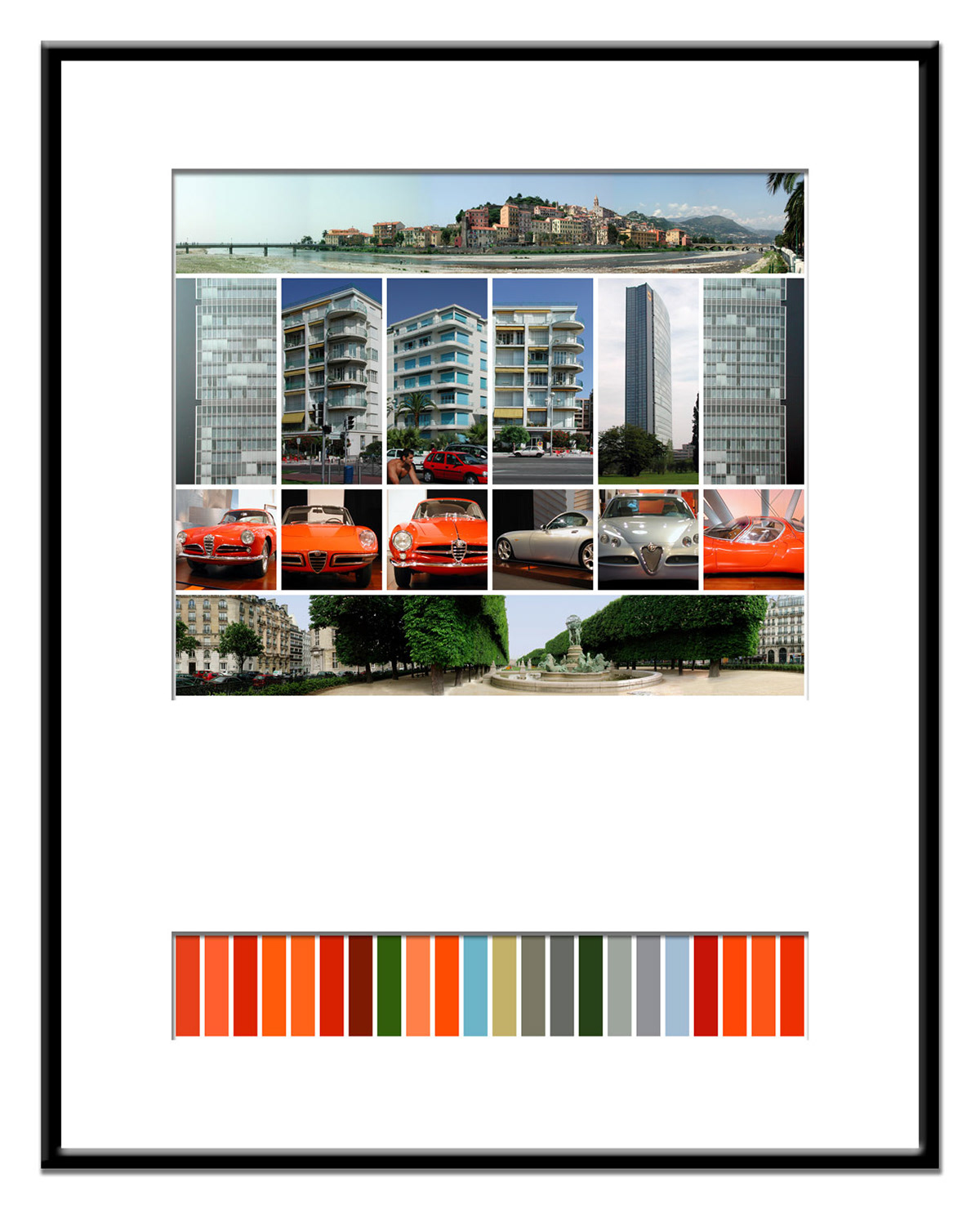

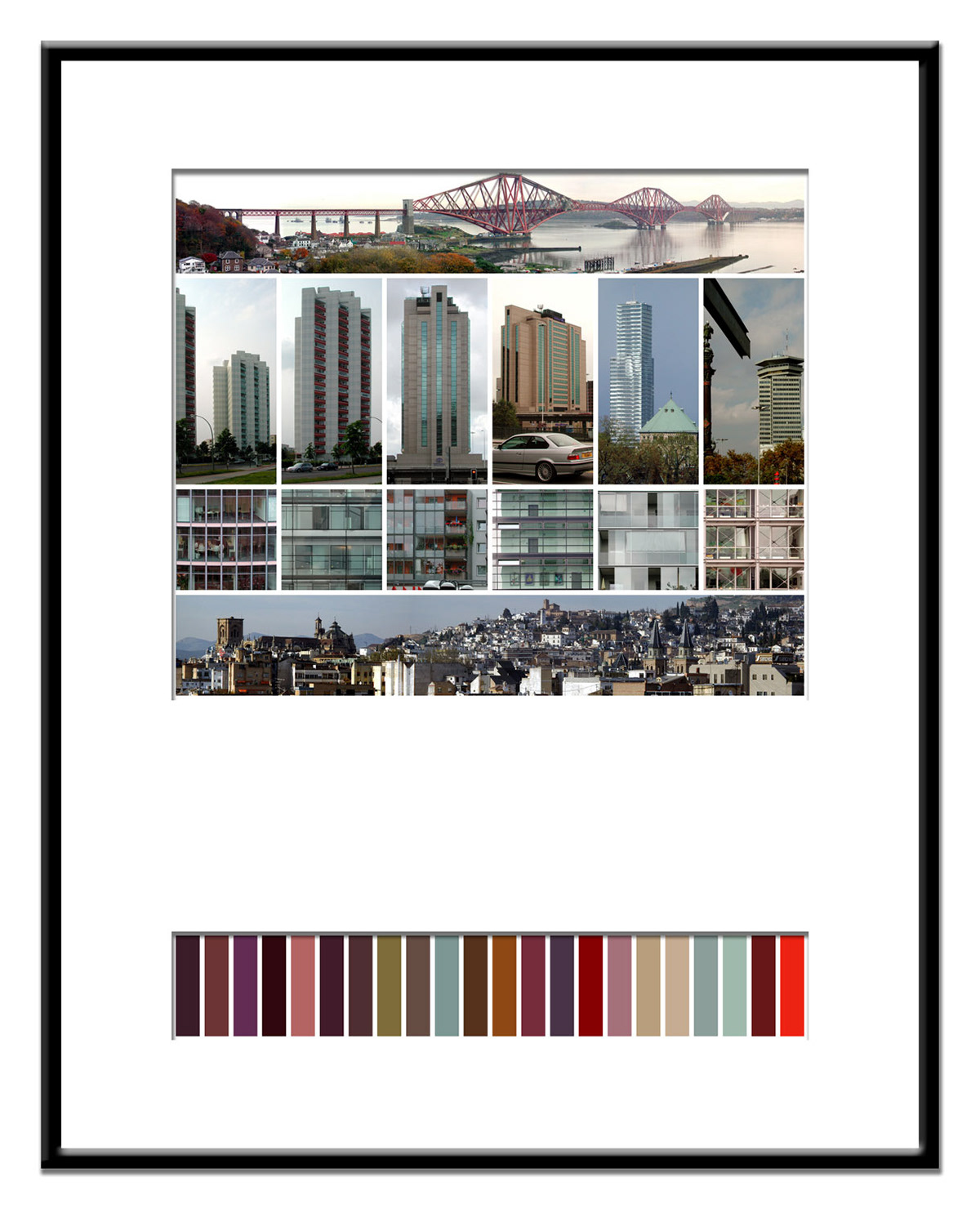

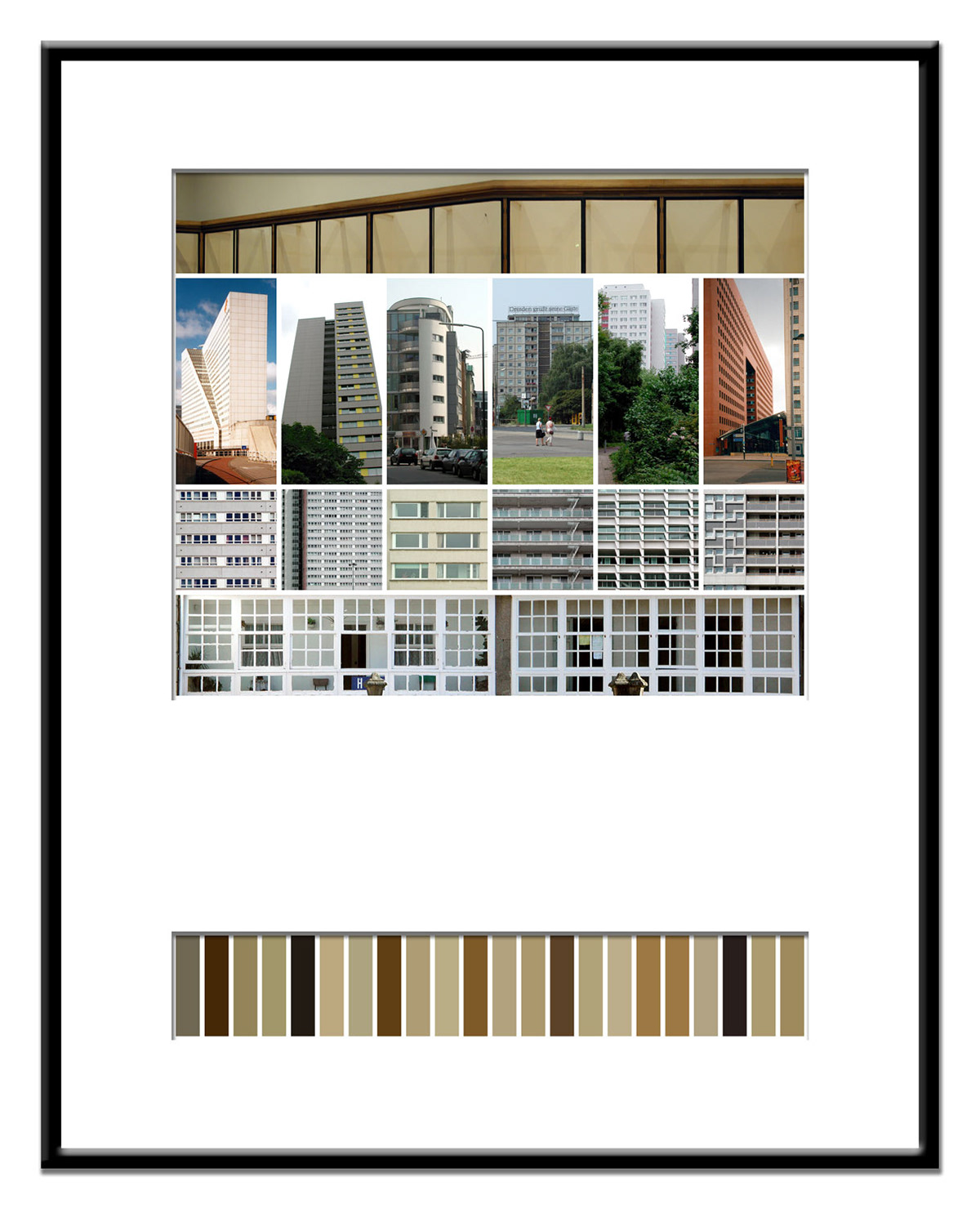

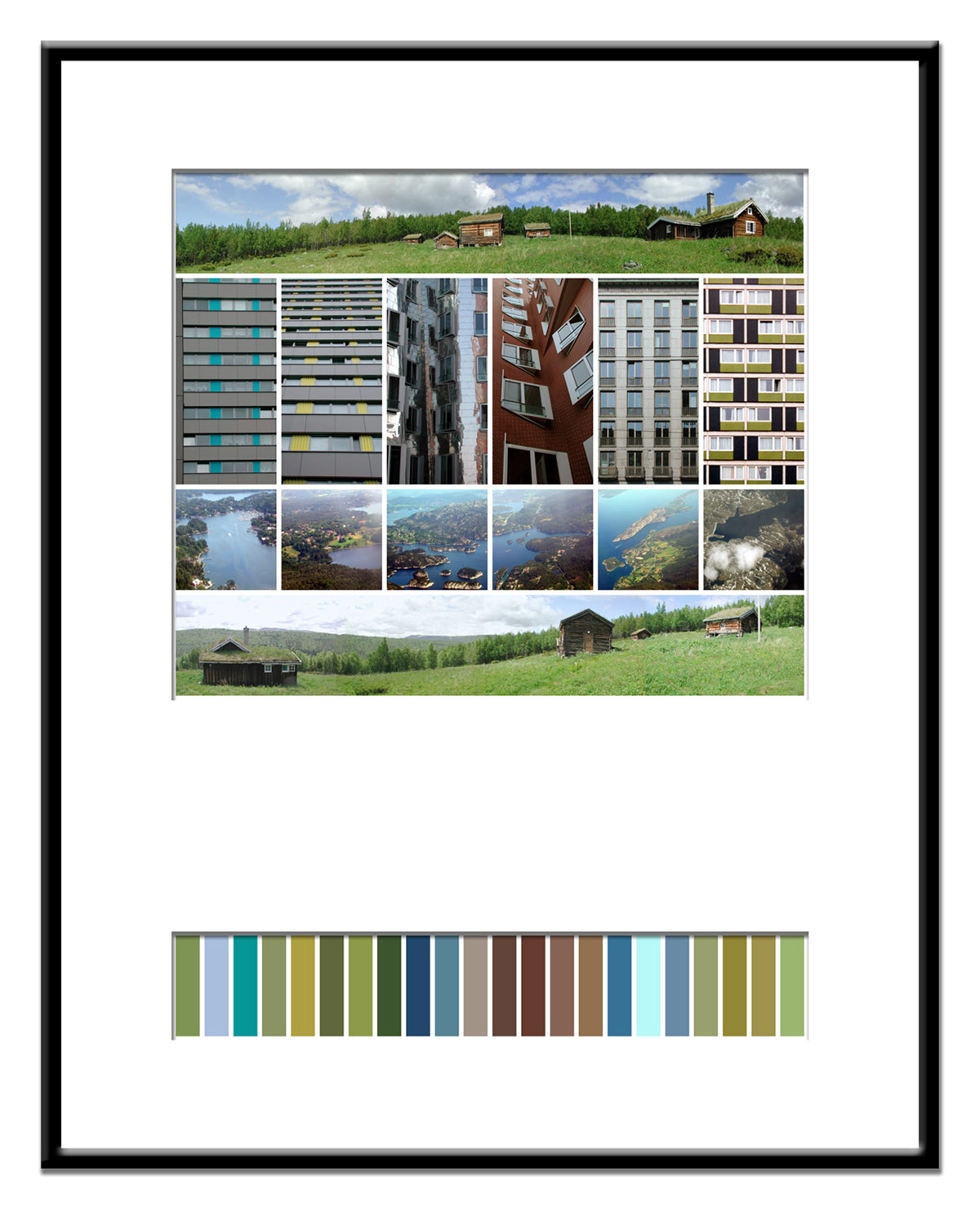

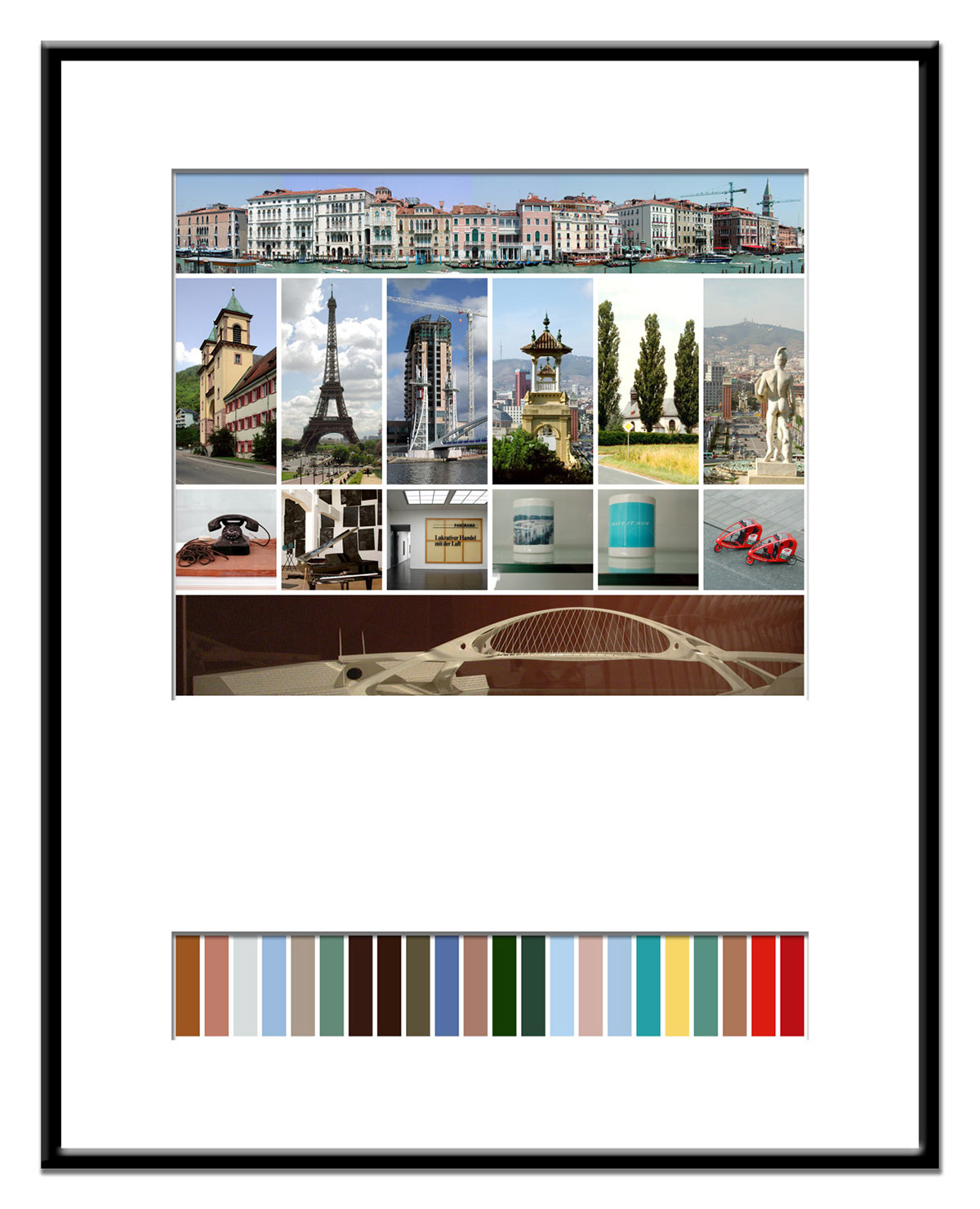

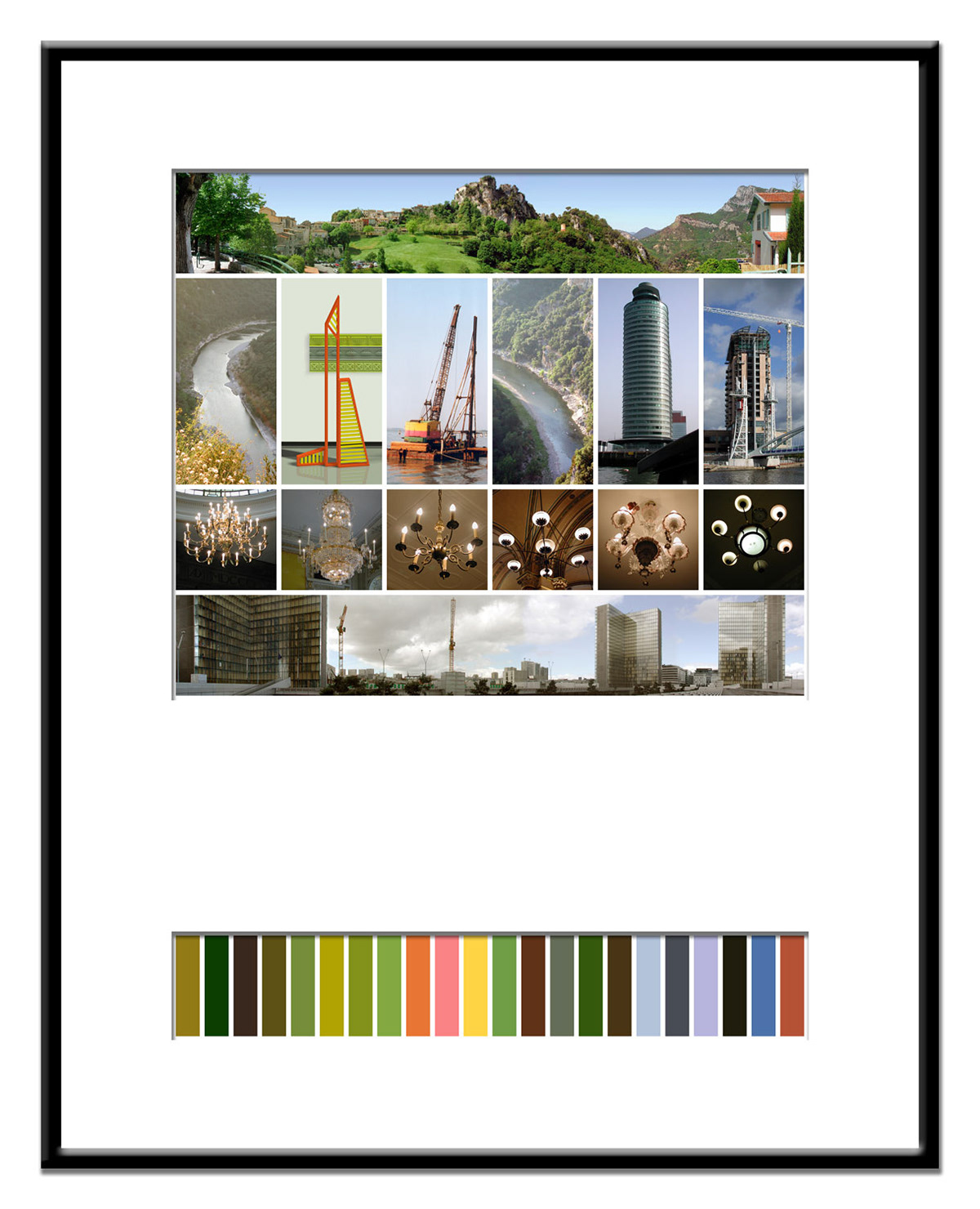

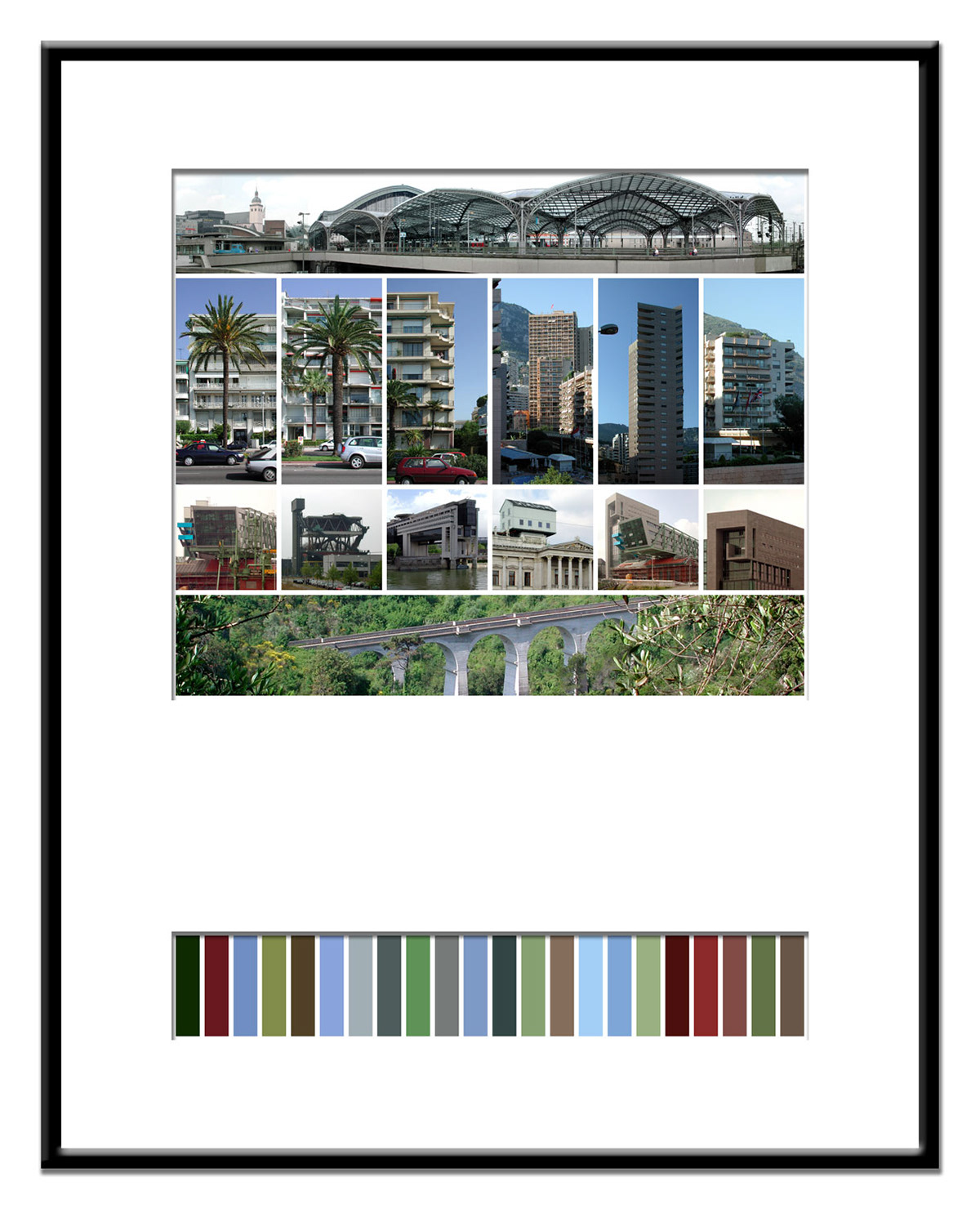

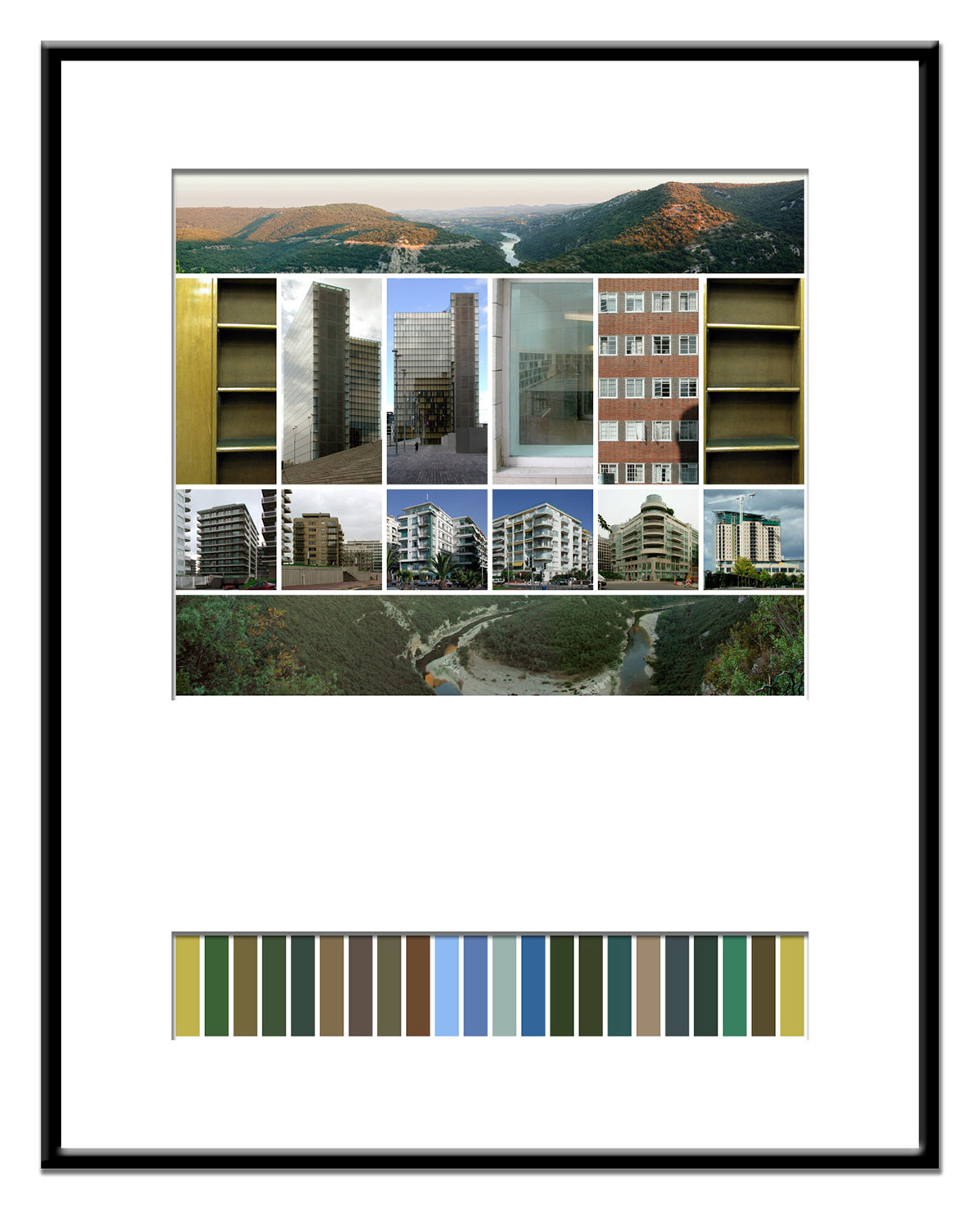

Colour Coded (2005)

Colour Coded gives the coloured stripes, which were already used in sketchy preliminary studies, a new function: as visual extractions from the respective groups of images, they appear below the composition like signatures or barcodes. The colour values are derived directly from the photographs used – precise, but not decorative. The series comprises 40 works and combines the principle of colour analysis with a clearly structured image composition. The process is later expanded and further developed in the Eight Albums albums.

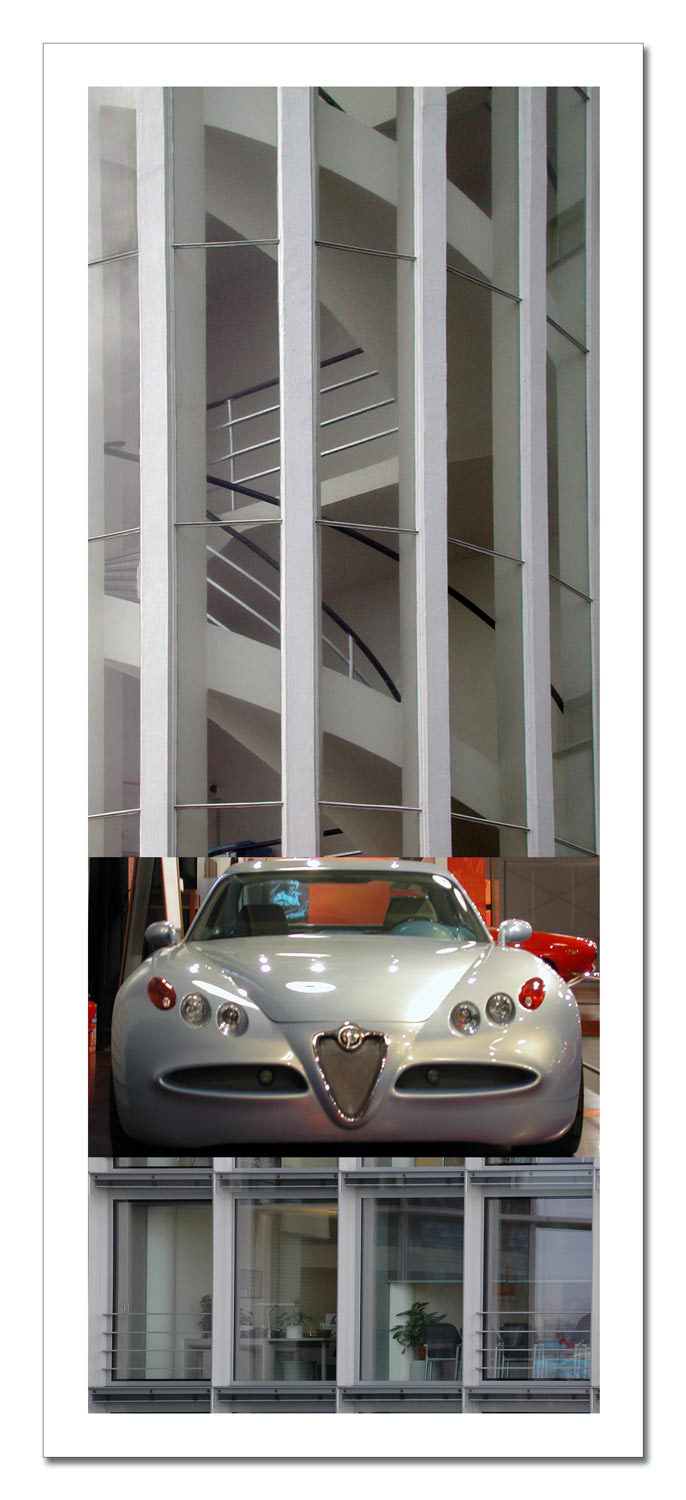

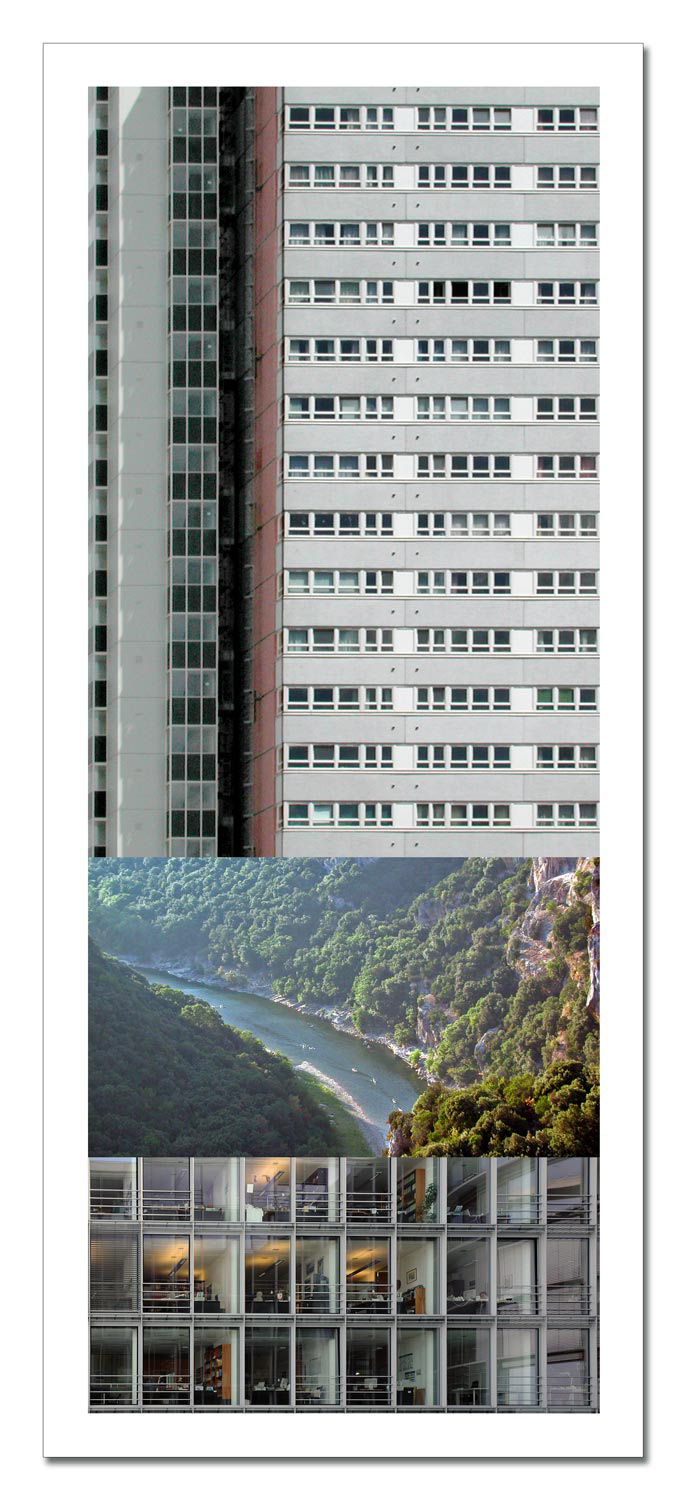

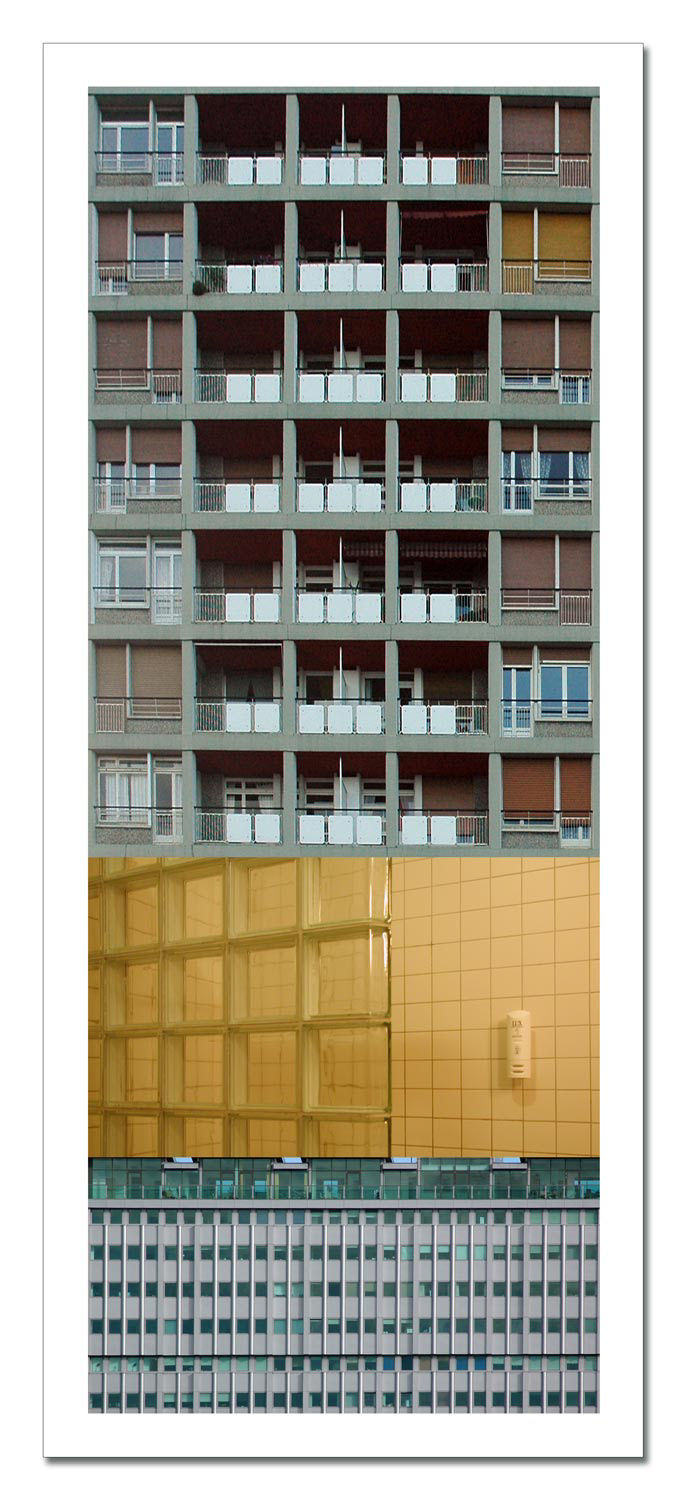

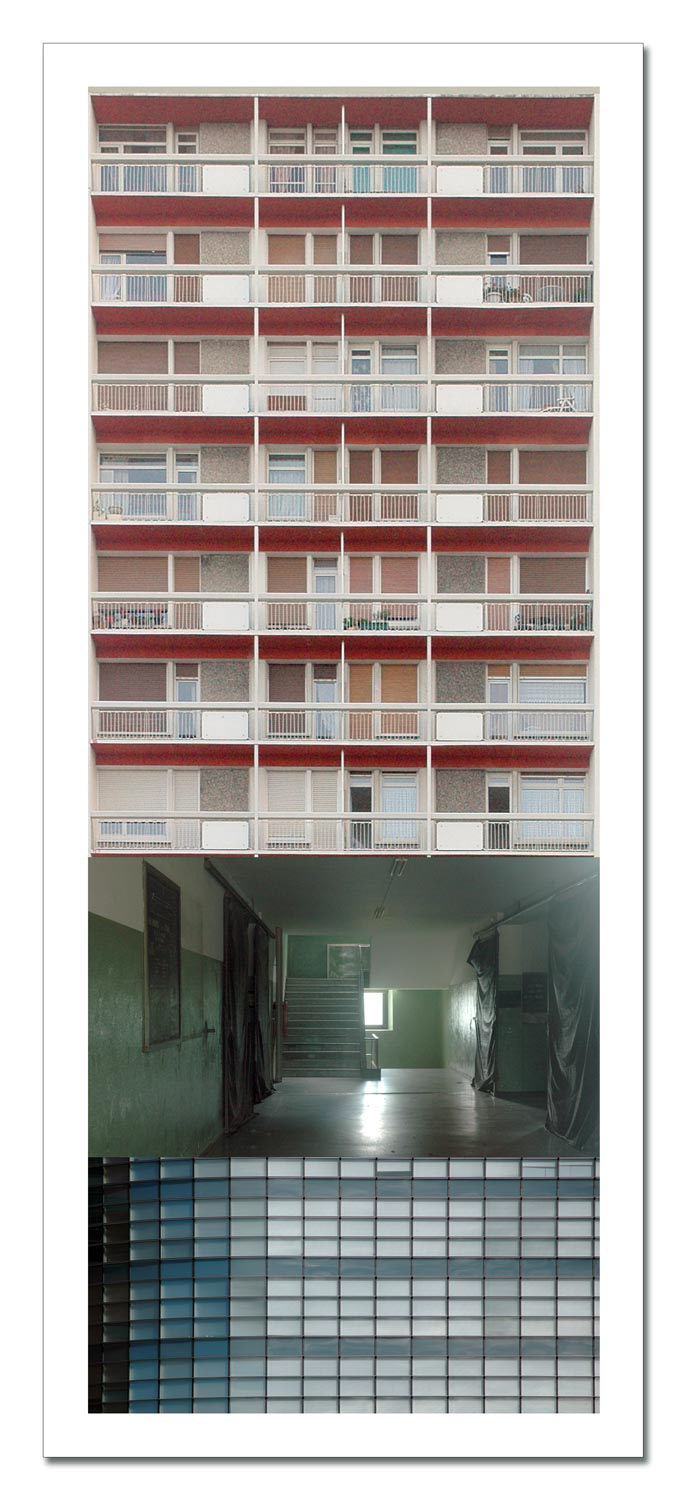

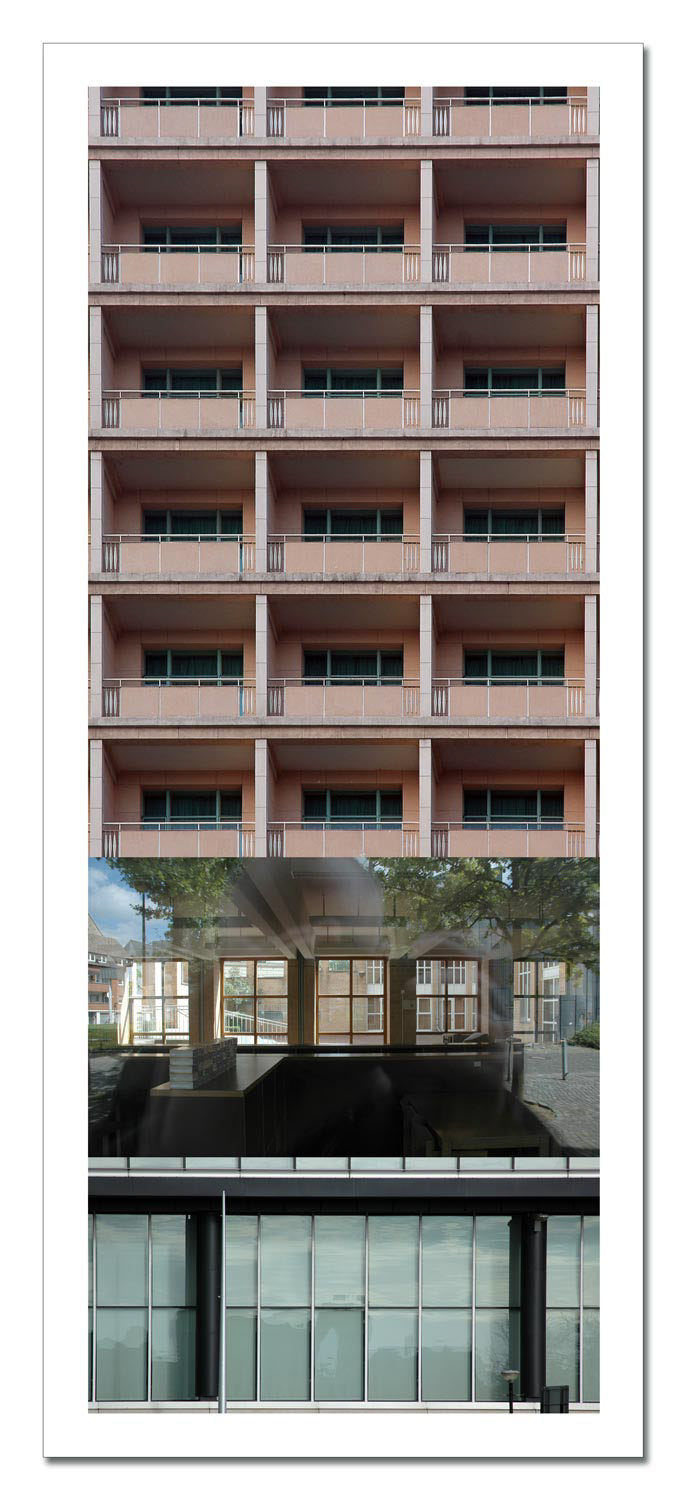

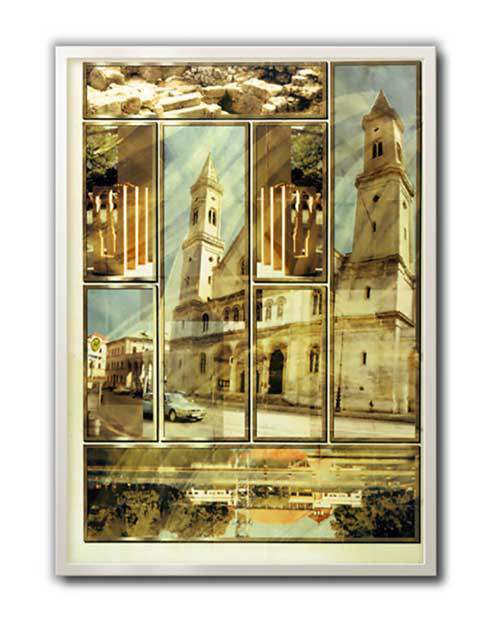

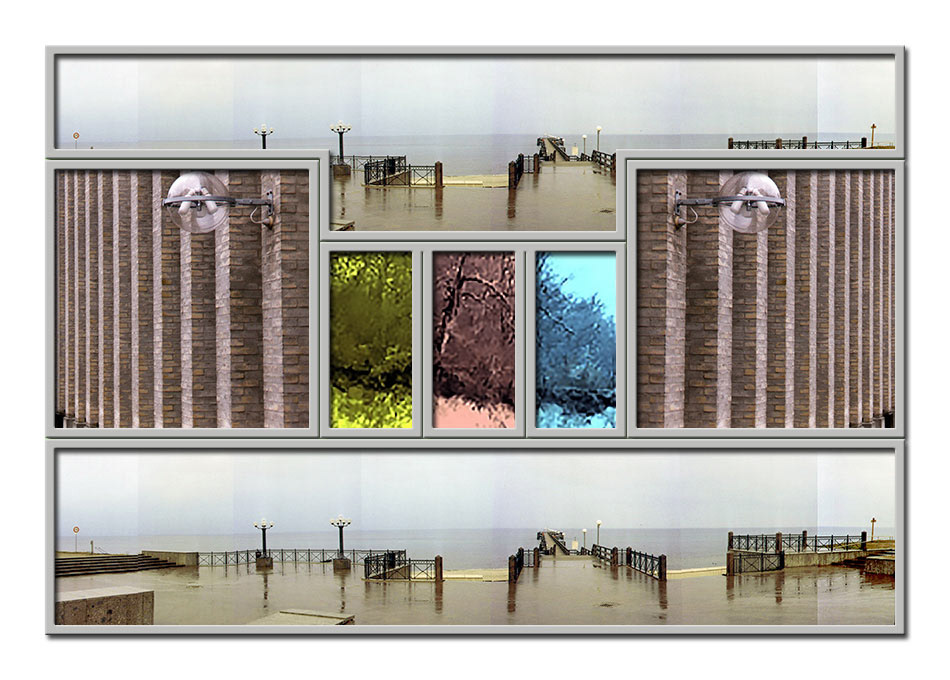

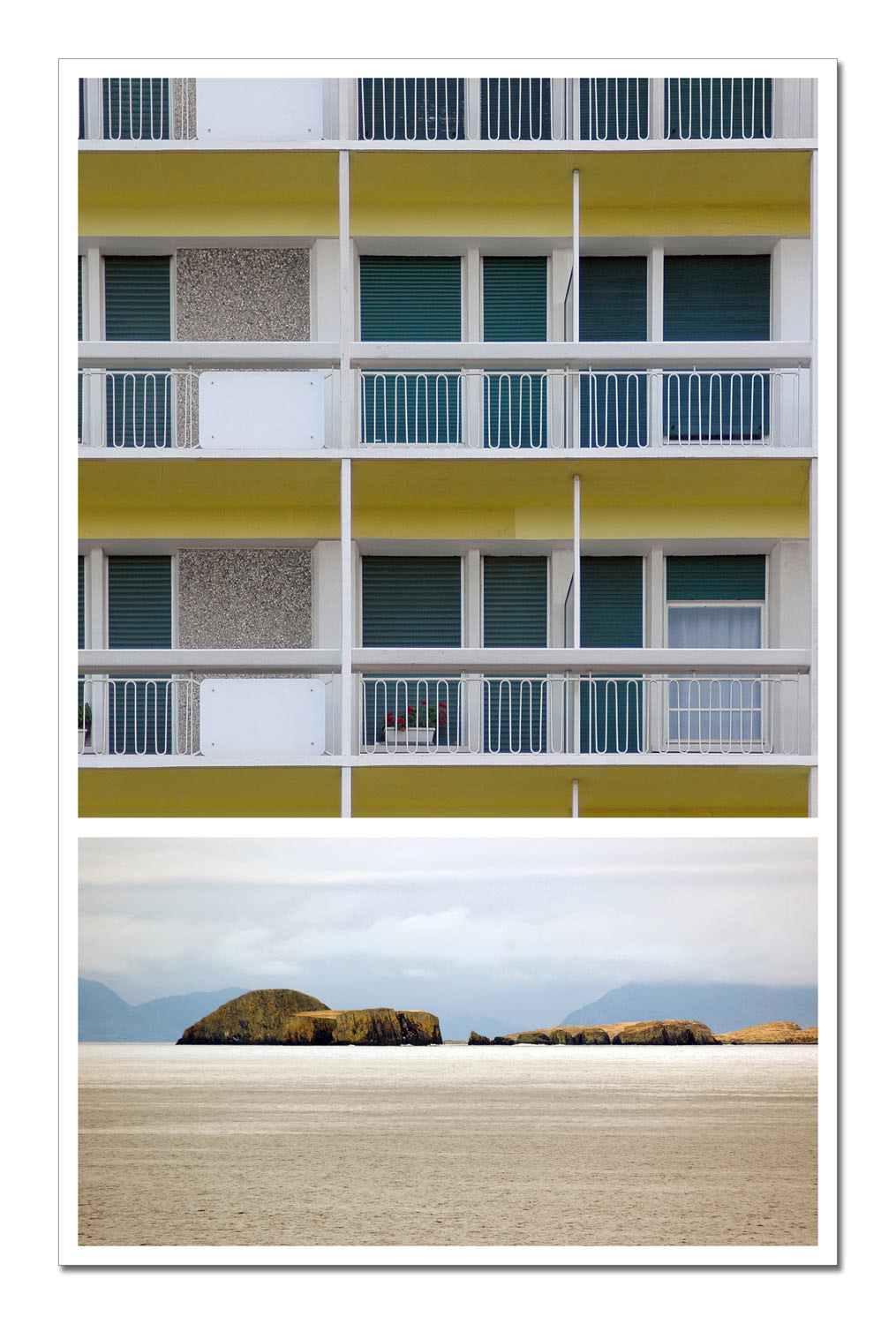

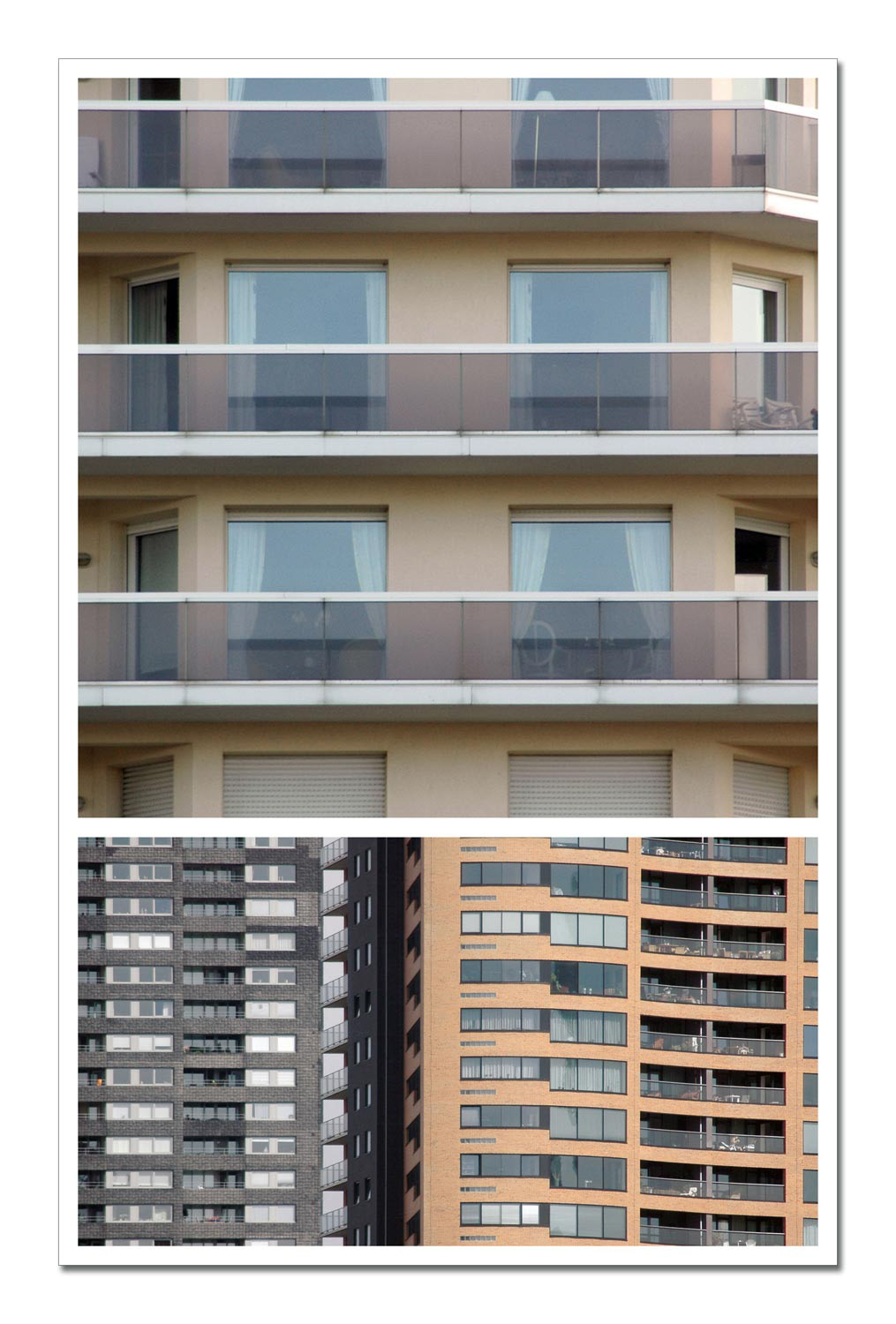

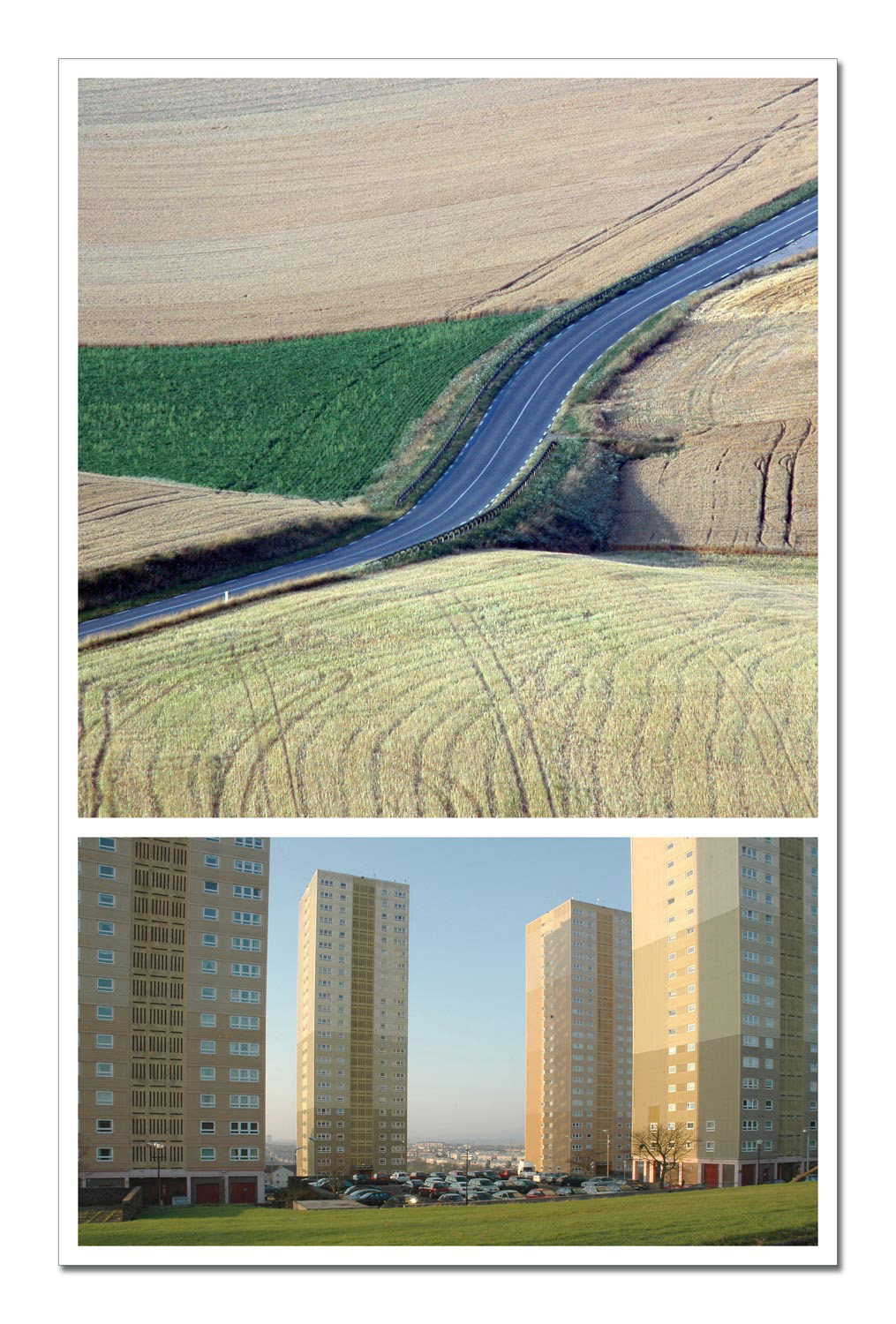

Binominal (2006-2008)

In addition to the panoramas, the archive is filled with countless individual photographs in portrait or landscape format. For the series zweigliedrig, two photographs are combined to form a new portrait format – without addition, without colour strips, without commentary. The combinations create quiet tensions and thematic frictions. The series comprises 32 works.

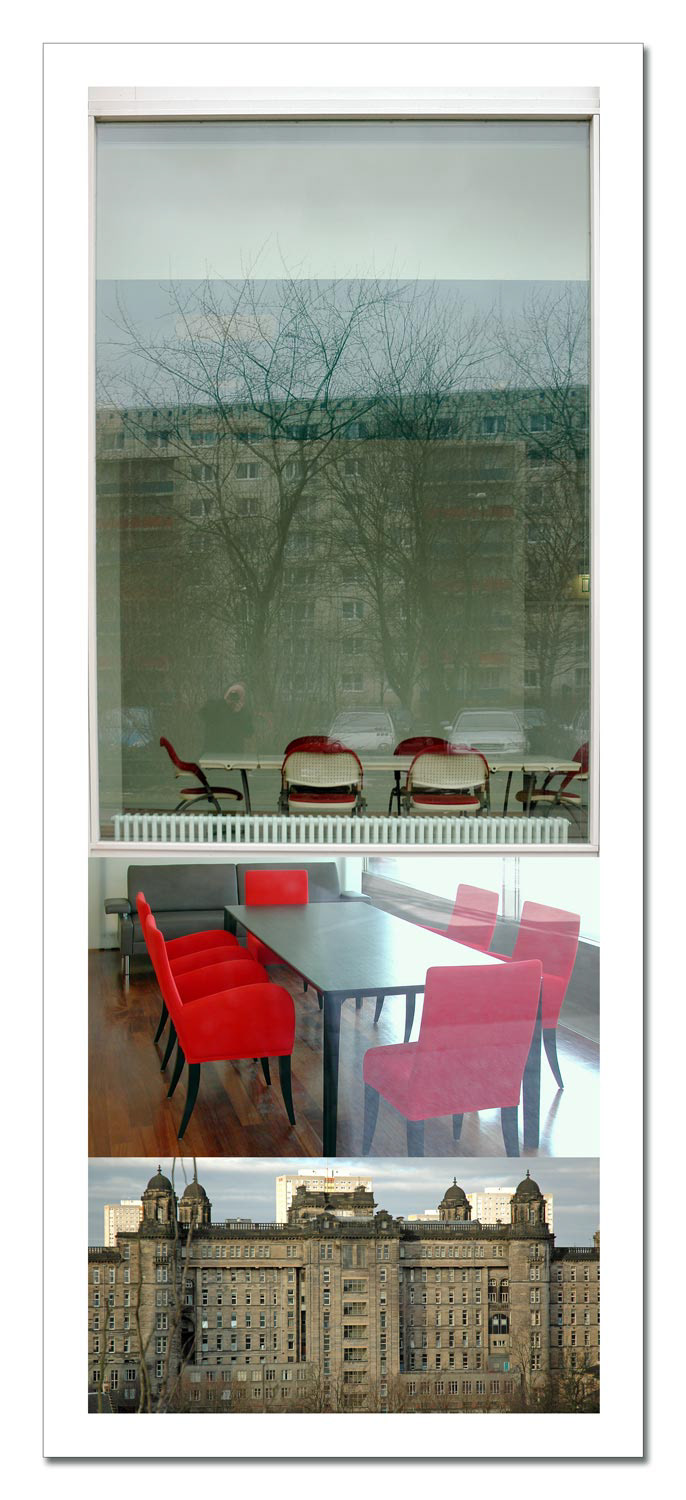

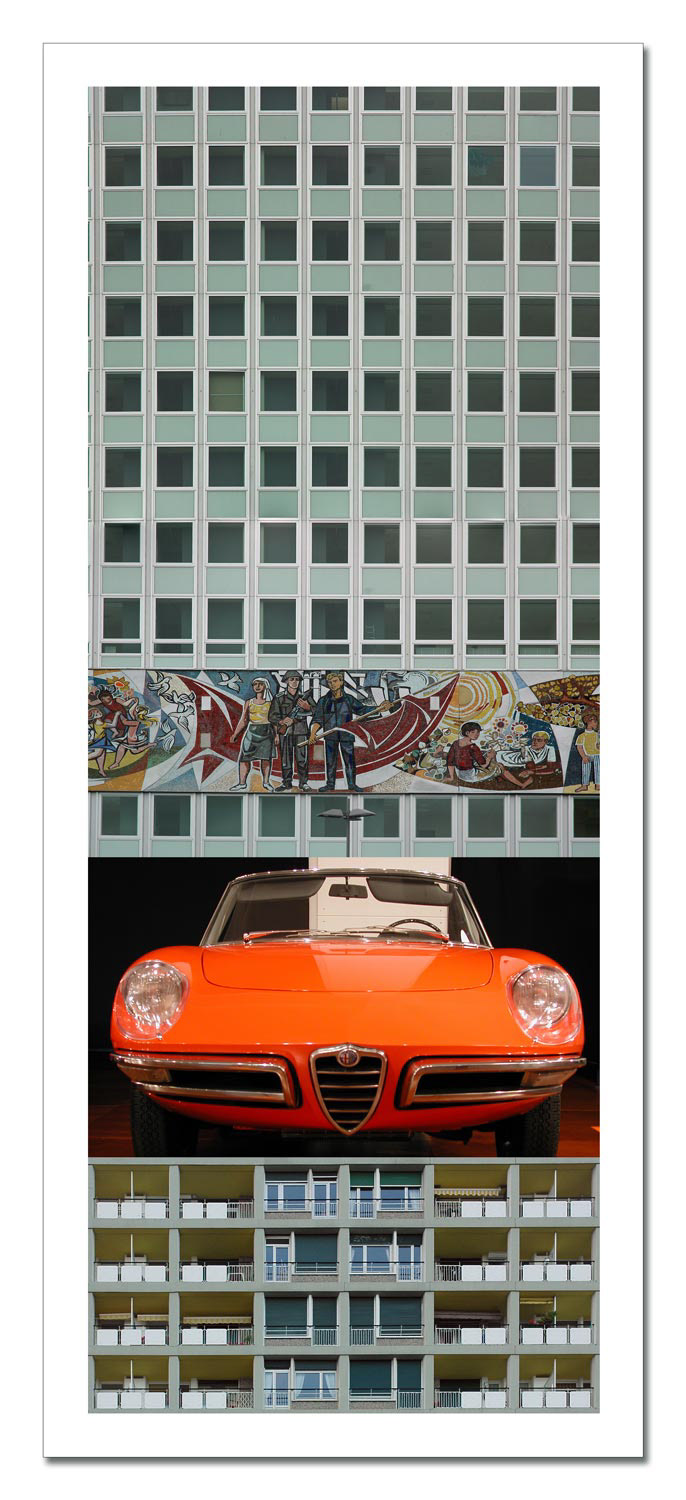

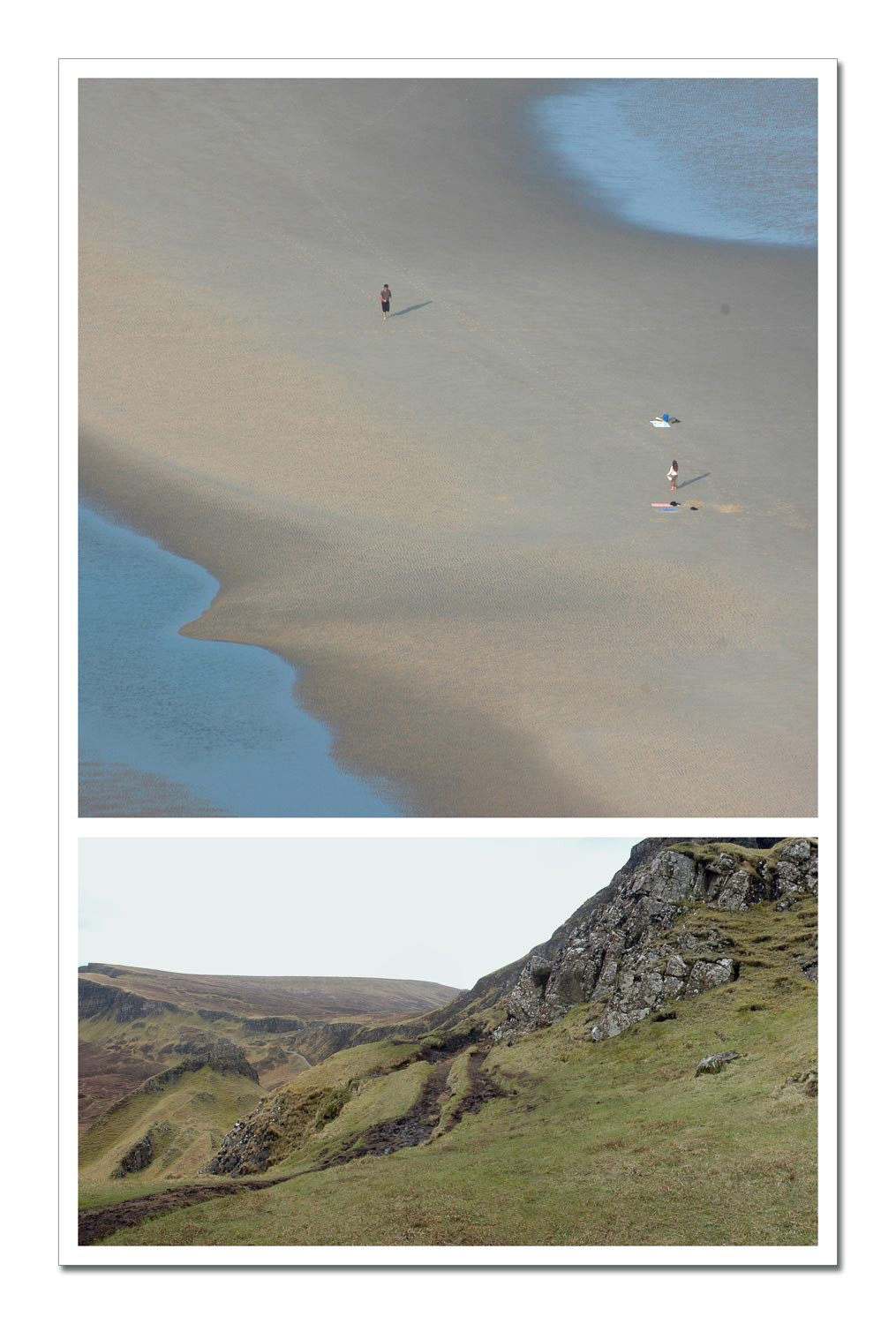

Trinominal (2006-2008)

In tripartite, a third image is added that separates two others. Top-centre-bottom or left-centre-right – the arrangement remains clear, but the content begins to shimmer. 140 of these compositions were created, which in their structural precision and motivic otherness are regarded as direct precursors of the later Eight Albums albums. The pictorial practice that unfolds after the move to Düsseldorf in 2009 takes its starting point here.